At the end of April an exclusive of the Wall Street Journal through satellite data showed a series of strategic movements of the Russian army on border enclaves. A few days before, the New York Times told how Finland was preparing for an eventual war. Then it was the Baltic countries that began to surround Russia with 600 bunkers.

Now all these countries have taken an unprecedented step.

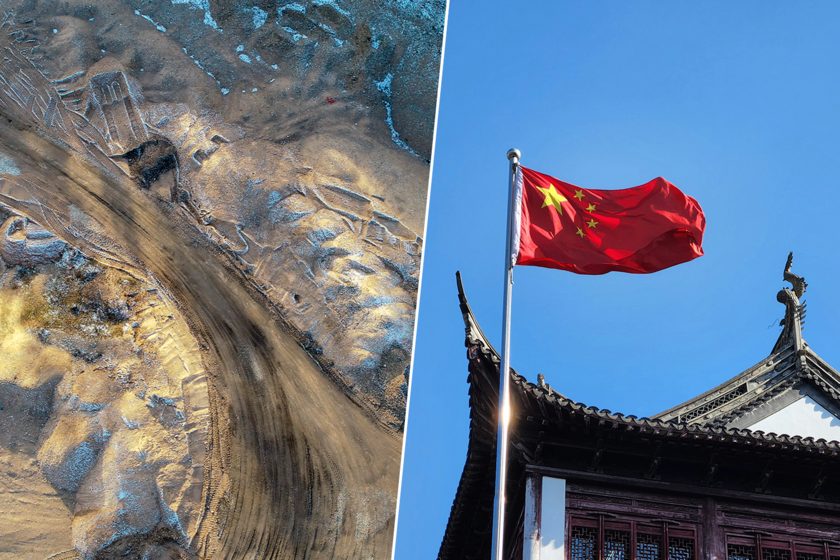

A shadow of the past. For decades, antipersonnel mines marked the borders of the Soviet block, not as much as an effective military defense, but as a brutal means of avoiding the flight of their citizens to the West. After the collapse of the USSR, the international community embarked on a complex and laborious demining campaign that culminated with the signing of the Ottawa treaty in 1997, backed by more than 160 countries.

It happens that this legacy of humanitarian disarmament, which seemed sealed forever, is now cracking. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, five European countries (Poland, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia) have decided to initiate the legal process to abandon the treaty, thus reopening the possibility of the systematic use of antipersonnel mines on European soil.

Military Pragmatism. The decision does not imply an immediate placement of mines on its borders, but it does mark a change of drastic approach and loaded with implications. For years, modern military doctrines minimized the tactical value of these weapons in conventional conflicts, underlining their indiscriminate character and scarce utility against armored units.

However, the war in Ukraine has altered that reasoning: the extensive mines fields placed by Russia were one of the decisive factors in the containment of the Ukrainian counteroffensive. Although they do not stop an mechanized division alone, they force the adversary to slow down their progress, channel their movements and spend valuable resources in cleaning operations, thus offering an asymmetric defensive advantage that many now see how inalienable.

Mina Antipersona Italian Valmara 69

Legal and moral consequences. The Ottawa treaty was more than a military pact signed by more than 160 countries (important: without Russia, China and the United States): it represented a moral milestone in the history of humanitarian law. Its success allowed to reduce the number of victims by mines from more than 20,000 a year in the 1990s to about 3,500 today. The departure of several European countries not only weakens the treaty in practical terms, but undergoes legal architecture that since the end of the Cold War has sought to humanize conflicts.

For many activists, such as Mary Wareham of Human Rights Watch, this withdrawal represents a dangerous crack in a consensus that also protects against chemical, biological and nuclear weapons. In his words, once the idea of abandoning international agreements gains legitimacy, it is difficult to stop the domino effect. What is at stake is not only a weapon, but the very principle that there are limits in war, he clarifies.

Blow to the heart of Europe. The pressure on governments has been intense and transversal. In Finland, whose Parliament voted for a large majority in favor of abandoning the treaty, even legislators contrary to the mines recognize that the fear of a Russian invasion has altered national security priorities. The 1,300 kilometers terrestrial border with Russia, together with a story marked by wars with Moscow, has generated a particular sensitivity that has given wings to proposals that just five years ago would have been unthinkable.

The political trigger, however, came from Lithuania, where the then Minister of Defense, after visiting Ukraine, said that the prohibition of the mines was hindering the defense against Russia. From there, the idea spread among the most exposed allies geographically. Only Norway, among the countries with a direct border with Russia, has reiterated its firm commitment to the treaty.

The past as a warning. Ukraine, signatory of the treaty in 2006, had kept more than three million mines in reserve. The frustration after the partial failure of his counteroffensive, together with the massive use of mines by Russia, led the Zelensky government to reconsider its position. In fact, the president formally announced the departure of the treaty, arguing that an existential threat could not be fought with a hand tied by treaties that Moscow never signed or respected.

The United States, although it is not part of the treaty, had maintained restrictions on the use of mines, but partially lifted them to supply Ukraine. This has marked a tacit break with decades of diplomatic efforts and disarmament. For many, such as the British Paul Heslop (UN expert), what we are witnessing is a betrayal to the memory of those who fought (and died) for eradicating these weapons.

Imagen | DFID, United Nations, PH1 Dewayne Smith

In WorldOfSoftware | Finland is the happiest country in the world. And is also preparing thoroughly for the most unhappy end: war

In WorldOfSoftware | Now we know what the US Army did in Finland. Russia is expanding its troops on its border with Europe