November 10, 2025

This is the fifth chapter of the report “Is Europe waking up to the China challenge? How geopolitics are reshaping EU and transatlantic strategy.” Read the full report here.

Germany’s relationship with China has evolved significantly over the past decades, with economic cooperation forming the backbone of bilateral ties. Its early posture toward Beijing mirrored its Cold War-era approach to trade with the Soviet Union—focused on pragmatic economic engagement despite political differences. As an outlier within the European Union (EU), Germany’s approach to China stood out for its industrial complementarity, mutual benefit, and limited political friction. This “win-win” model, formalized in a 2004 strategic partnership and upgraded to a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2014, fueled prosperity but also deepened dependency, shaping the EU’s broader asymmetry in dealing with China.

The first disagreements emerged over human rights issues in Tibet and Xinjiang, but economic interest prevailed under Chancellor Angela Merkel’s “Wandel durch Handel” (“change through trade”) doctrine, which assumed that engagement with authoritarian regimes would eventually spur political liberalization. By 2016, China had become Germany’s largest trading partner, and its acquisitions of strategic firms such as Kuka and Aixtron triggered alarm over technological vulnerabilities. The Federation of German Industries (BDI) framed China as a systemic competitor in 2019, helping shape the EU’s “partner, competitor, rival” approach that same year. Merkel, however, continued to prioritize engagement, championing the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) during Germany’s 2020 EU Council Presidency.

The 2020s brought a reckoning. The pandemic, supply chain shocks, and Beijing’s increasing alignment with Moscow exposed the risks of overreliance. In 2021, Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s government included the term “Taiwan” in its coalition agreement for the first time and openly framed China as a rival. Berlin’s 2023 China Strategy marked a cautious pivot—reducing dependencies and emphasizing competition while preserving cooperation on global challenges.

Under Chancellor Friedrich Merz, Germany has aligned more closely with the EU’s “de-risking” agenda, dropping the term “partnership” from its China rhetoric and stressing competition and rivalry. Yet domestic resistance and corporate lobbying have slowed this shift. Today, Germany’s China policy mirrors the EU’s broader evolution—from optimism to caution, and from partnership to rivalry. As Europe’s largest economy and a key driver of integration, Berlin’s choices shape the EU’s China policy, even as its approach remains reactive, constrained by economic dependence, transatlantic expectations, and European ambitions.

Trade and investment: From growth engine to rivalry

Germany’s engagement with China dates back to the late nineteenth century, when it seized Jiaozhou Bay—home to the city of Qingdao—and began investing heavily in the colony’s infrastructure and industry. After decades of turbulent relations, the two countries established diplomatic ties in 1972, with a primary focus on economic cooperation. In the years that followed, Germany and China built a close trade relationship, grounded in extensive exchanges of goods and industrial complementarity. The German industry supplied cars, machinery, chemicals, and engineering know-how that fueled China’s growth while sustaining high-paying jobs at home, making Germany the EU’s growth engine.

Trade has grown by more than 900 percent since 2001—from $27 billion to $273 billion in 2024—with Germany accounting for 35 percent of total EU-China trade. While the United States was still reeling from the surge of low-cost Chinese imports and China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO), Germany thrived on Chinese demand, particularly in the automotive, machinery, and chemical industries. This complementarity allowed German firms to weather economic shocks better than their peers—a rare “win-win” scenario. As an outlier within the EU, Germany stood out for its emphasis on industrial cooperation and limited political confrontation. The “win-win” relationship—with Germany exporting advanced technologies, luxury cars, and high-end products, and China supplying inexpensive consumer goods—created a structural imbalance in Europe’s engagement with China.

The first major rift between Berlin and Beijing arose over human rights issues in Tibet and Xinjiang, as well as Chancellor Angela Merkel’s 2007 meeting with the Dalai Lama, after which China suspended the Sino-German Rule of Law Dialogue. Despite these tensions, Berlin’s China policy remained rooted in Merkel’s “Wandel durch Handel” approach, emphasizing broad cooperation agreements intended to balance economic interests with Germany’s values-driven foreign policy. In the years that followed, China surpassed the United States to become Germany’s largest trading partner—initially fueling cautious optimism but later prompting alarm over Chinese acquisitions of high-tech firms such as Kuka and Aixtron.

By 2020, the tables had turned. Chinese imports to Germany jumped 98 percent between 2020 and 2022 (from $105 billion to $208 billion), while German exports fell by 10 percent (from $110 billion in 2020 to $98 billion in 2024). Import growth slowed in 2024 as Berlin ended electric vehicle (EV) purchase subsidies and the EU imposed tariffs of up to 45 percent on Chinese EVs. Yet Germany still posted a $77 billion trade deficit, marking the end of balanced trade. Today, China is Germany’s top import partner (13 percent of total imports) but only its fifth-largest export market (6 percent of total exports). By 2024, China’s cumulative foreign direct investment (FDI) in Germany reached $35 billion, making it Germany’s tenth largest investor. That same year, China ranked as Germany’s third largest source of new FDI projects, while German FDI in China climbed to $80 billion—accounting for nearly 60 percent of all EU investment there.

The strain of this new relationship is most visible in the automotive and machinery sectors, while industries where China still lags—such as measurement equipment and pharmaceuticals—remain relatively resilient for now. China’s imports of German auto parts fell 22 percent between 2021 and 2023, signaling a weakening of industrial linkages. A partnership that was once mutually beneficial has become marked by asymmetry, intensified competition, and geopolitical strain.

As a result, Berlin has recalibrated its approach to China—a shift driven primarily by three factors: China’s rapid ascent up the value chain, its economic slowdown, and rising geopolitical risks. Beijing’s industrial push, crystallized in its “Made in China 2025” plan, was reinforced by a surge of acquisitions of European firms. Chinese FDI in Europe peaked at nearly $40 billion in 2016, including $12 billion in Germany alone.That year, Merkel warned that China was emerging as an economic rival, while Beijing pressed for WTO market-economy status to weaken European trade defenses.

The European Parliament, European industry, and labor unions—led by the steel sector mobilized in opposition, marking the EU’s first coordinated pushback. In 2019, the BDI publicly labeled China as a “systemic competitor,” issuing fifty-four policy demands, which urged the EU to reduce its dependence on the Chinese market, strengthen industrial policy, and ensure trade reciprocity. Merkel nonetheless continued to pursue engagement, using Germany’s 2020 EU Council Presidency to advocate for the CAI. She worked closely with French President Emmanuel Macron, presenting the effort as “strategic autonomy,” partly to shield European industry from the unpredictability of the first Trump administration and in response to pressure from German corporations deeply invested in China. Although Merkel never called China a “rival,” the BDI’s leadership helped steer Europe toward a more sober and defensive stance.

As the 2020’s ushered in the COVID-19 pandemic and exposed global supply chain vulnerabilities, Russia’s war in Ukraine and Beijing’s alignment with Moscow underscored the need for “de-risking” and diversification. Germany began reducing vulnerabilities while avoiding full decoupling, seeking to preserve dialogue even amid growing tension. In 2021, the newly-elected German government introduced tougher language on China, referencing Taiwan in its coalition agreement and framing China as a rival. Moreover, Germany’s 2023 China strategy seeks to cut dependencies in critical sectors, protect infrastructure, and counter espionage, while maintaining cooperation on global challenges such as climate change. Chancellor Olaf Scholz has combined criticism of market barriers and Chinese industrial overcapacity with acknowledgment of China’s importance for energy transition and innovation—signaling a pragmatic balancing act between German economic interests and continuity.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s “de-risking” agenda aligns with Berlin’s rhetoric as codified in its 2023 strategy. Yet many multinationals interpret this approach as deeper localization in China rather than genuine diversification. The “Mittelstand”—Germany’s small and medium-sized enterprises—faces intense competition as Chinese firms, having mastered their technologies, now outcompete them. With limited government support, de-risking remains more slogan than strategy.

In November 2022, a group of leading German business executives warned in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung that de-risking had gone too far, arguing that access to the world’s second largest market remains vital for competitiveness and jobs. This position echoed Scholz’s emphasis on reducing one-sided dependencies without full “decoupling,” contrasting sharply with Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock’s much tougher stance on China—underscoring divisions within the coalition of the chancellor’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the foreign minister’s Green Party. Beijing, in turn, dismissed de-risking as “decoupling by another name,” while Premier Li Qiang assured German industrialists that “failure to cooperate was the biggest risk.”

By 2025, awareness of risks had sharpened. Even trade unions such as IG Metall began pressing for measures once considered taboo. Protectionist instruments multiplied, signaling a major shift in industrial thinking. Still, divisions persisted. While the chemical and machinery sectors adjusted, the German automotive industry opposed tariffs on Chinese EVs, fearing the loss of key markets. As a result, Germany voted against broad EU tariffs. Rather than retreating, German firms doubled down on an “in China, for China” strategy, embedding production, research and development (R&D), and supply chains in the People’s Republic to remain competitive and shield against political shocks. In its 2023/24 survey, the German Chamber of Commerce in China found that over 90 percent of its members planned to maintain operations, with more than half intending to expand. In 2024, German firms invested €5.7 billion in China—accounting for 45 percent of EU and UK FDI in the country—with the automotive sector responsible for nearly three-quarters of the total investment. In that sense, Germany’s China playbook is shifting from economic complementarity to managed exposure: selective corporate deepening inside China to stay competitive, paired with EU-German derisking at home.

Technology: Industrial innovation and strategic exposure

Germany’s technological ties with China are characterized by a mix of cooperation and competition. What began as one-way technology transfer has evolved into partnerships: German firms co-develop and localize advanced technologies in China—especially EVs, smart manufacturing, and green systems—while collaborating on Industry 4.0 standards and interoperability. Chinese technological upscaling and import-substitution are displacing foreign suppliers and eroding German market share in EVs, batteries, machine tools, and industrial software driven by artificial intelligence (AI), both in China and in third markets.

Berlin has responded with de-risking, stricter investment screening, and trade defenses. Meanwhile, Germany’s large corporations have adapted through greater integration with the Chinese market, via “in China, for China” localization, “dual play” strategies, parallel supply chains, IP ring-fencing, and selective alliances. Viewing China as an innovation hub, German firms are localizing R&D and supply chains within the country to leverage scale and speed. Initiatives such as the Sino-German Standardization Innovation Center in Frankfurt, launched in 2025, promote industrial coordination and signal a commitment to building a joint technology ecosystem. Still, there is no one-size-fits-all corporate strategy, as the case of Infineon, Germany’s leading semiconductor company, illustrates. Infineon is pursuing a strategy of “targeted deepening,” carefully expanding ties with China to meet market demand while navigating the strategic sensitivities of semiconductors.

With regard to foreign investment screening, the 2016 takeover of German robot maker Kuka by the Chinese Midea Group was a turning point for Germany and the EU, highlighting Europe’s lack of defenses against strategic acquisitions in robotics and Industry 4.0. This triggered a chain reaction: amendments to the Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance in 2017 tightened the national screening regime, lowering the threshold for when foreign acquisitions must be reviewed. In 2021, the rules became even stricter—any attempt by a foreign buyer to acquire more than 10 percent of a sensitive company can now trigger government scrutiny.

The main concern is that US chip controls combined with China’s rapid AI advances are accelerating a global tech split, leaving Germany squeezed and potentially falling behind in key technology fields. In July 2024, Berlin decided to exclude Chinese companies such as Huawei and ZTE from its 5G network products, aligning its telecom security policy with EU guidance after years of delay. A previous push by members of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) to exclude Huawei from 5G, considering it a national security issue, had been blocked by Merkel, who maintained that no vendor should be barred if it met security requirements. Ultimately, Berlin adopted the EU’s 5G Toolbox as the framework for its approach. However, the fact that Huawei still accounted for 59 percent of Germany’s 5G RAN equipment and 57 percent of its 4G network in 2022 shows how firmly Chinese technology remains embedded in the country’s critical infrastructure.

The German auto industry’s “China shock”

Many in Germany consider automakers the country’s economic lifeblood. With this in mind, it seemed rational to establish a market presence in China, entering the country in the 1980s through joint ventures that exchanged technology transfer for market access. There is little doubt that with this approach, Germany played a central role in developing China’s automotive sector. By 2009, China had overtaken the United States as the world’s largest automotive market, with German companies operating over 350 sites.

One outcome of Germany’s engagement in China was the transfer of technological knowledge and manufacturing expertise. Combined with Beijing’s heavy subsidies and industrial strategies—“Made in China 2025,” dual circulation, and dual carbon policies— China had built a complete EV value chain by 2015, while Germany remained largely tied to the combustion engine. By 2024, nearly half of China’s car sales were electric, representing two-thirds of global EV sales. Chinese brands like BYD, Geely, and NIO surged, with BYD surpassing Volkswagen as China’s best-selling brand.

The consequences for German firms were severe. Between 2022 and 2024, exports to China plunged 70 percent, while foreign automakers’ market share dropped from 53 percent to 33 percent. Yet since 2019, German companies had produced more cars in China than at home, increasingly relying on local suppliers and investing in Chinese EV and battery makers. In 1992, China produced approximately one million vehicles per year—by 2024, it reached 31 million, with roughly 40 percent (thirteen million units) classified as new energy vehicles (NEVs). China maintained its lead among major markets, with electric car sales exceeding 11 million—more than the global total just two years earlier. By 2025, its annual NEV production capacity is projected to reach twenty-five million vehicles, surpassing the combined output of Germany, Japan, and the United States.

With domestic demand unable to absorb this output, Chinese automakers are targeting global markets, including Europe, where BYD and NIO are gaining ground. For Germany, long reliant on China as its largest automotive market, this shift is a direct threat. Chinese firms now dominate at home and are challenging German manufacturers in Europe. Germany’s automakers thus face a dual squeeze—shrinking margins in China and rising competition from Chinese EVs worldwide.

Security: Responding to China’s global ambitions

Germany’s security outlook has shifted markedly in recent years, shaped by growing concerns over espionage, cyberattacks, and Beijing’s global assertiveness. Chinese hacking campaigns targeting German institutions—from the Federal Agency for Cartography to CDU party headquarters—have become routine. High-profile espionage cases in 2024 and 2025, including arrests of parliamentary aides, put Berlin’s security community on high alert. These incidents reinforced political support for stricter investment screening and raised doubts about whether China could still be treated as a straightforward “partner.”

In 2021, the Scholz administration signaled both continuity and change in its China policy. While building on Merkel’s approach, the coalition agreement adopted noticeably sharper language—describing China as a “partner, competitor, and systemic rival,” and making it the first official document to explicitly label Beijing a “rival.” Moreover, the coalition agreement explicitly mentioned Taiwan, marking a significant departure from past practice. Under Merkel, Taiwan had been entirely absent from Germany’s so-called policy guidelines for the Indo-Pacific, which framed the region in economic and multilateral rather than security terms. By contrast, the Scholz government’s 2024 progress report on the implementation of guidelines referenced Taiwan at least five times.

In July 2023, Germany published its first dedicated China strategy, despite internal disputes between the Greens’ Foreign Ministry and the SPD-led Chancellery. The Greens advocated a values-based, critical stance on China, while Scholz’s party favored a pragmatic, trade-oriented approach centered on stability and engagement. The final document underscores China’s “systemic rivalry” but also notes that addressing global challenges requires cooperation with Beijing. Notably absent, however, is the EU’s “partner, competitor, rival” formula. Instead, the strategy omits any reference to “partner,” referring only to “cooperation.” The 2025 coalition agreement under Chancellor Merz commits to further revising the strategy “according to the principle of de-risking,” with greater emphasis on defense, cyber, infrastructure, and disinformation.

Germany’s understanding of “rivalry” has also evolved. While it initially referred primarily to China’s authoritarian governance, it now encompasses Beijing’s challenge to the international order itself. China is no longer seen as merely more assertive, but as actively seeking to reshape global rules, promote multipolarity, and advance Beijing-centric frameworks—as illustrated by its ten-point paper on Ukraine. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine exposed the dangers of dependency on autocratic powers, prompting Berlin to stress resilience in critical technologies, supply chains, and democratic institutions. Critics of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline—built to carry Russian gas directly to Germany through the Baltic Sea—were vindicated, recalling earlier warnings that Vladimir Putin would weaponize energy.

Since then, military developments have added further urgency. German Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul has warned that China’s assertive posture in the South China Sea threatens not only stability in Asia but also the international rules-based order and Europe’s economic lifelines. Beijing’s continued support for Russia throughout its war in Ukraine has deepened perceptions of systemic rivalry, fusing security concerns with the economic risks of overdependence on China.

New measures adopted in 2025 further illustrate this shift. The KRITIS law, implementing an EU directive, obliges operators of critical infrastructure in energy, transport, finance, health, and water to secure their installations against sabotage and cyberattacks. While prompted by Russia’s aggression and recent sabotage incidents, the law also reflects mounting concern over Chinese cyber operations.

Germany’s alignment with the EU’s China policy

While Germany’s China policy broadly aligns with the EU’s overall approach, Berlin has also played a pivotal role in shaping Brussels’ strategy from the outset—emphasizing economic engagement and industrial competitiveness. In response, Beijing has adopted a “twin-track” strategy, offering Germany reassurance and high-level access while simultaneously pushing back at the EU level with countermeasures when trade, defense and technology controls impinge on its interests.

On the economic front, Germany was instrumental in shaping the EU’s “partner, competitor, rival” framework on China. While Chancellor Merkel resisted the term “systemic rival,” preferring to emphasize competition alongside partnership and cautioning against demonizing China for its success, the BDI helped frame China as a competitor. Berlin promoted a balanced approach—addressing unfair competition and limited market access without isolating Beijing.

Germany also shaped EU trade and investment policy, most notably by advancing the CAI after seven years of stalled talks. During Germany’s presidency of the Council of the EU in late 2020, Merkel made CAI a priority, urging the Commission to accelerate negotiations and securing an “agreement in principle” on 30 December, 2020. While this demonstrated Berlin’s influence in EU policymaking, it also exposed divisions within the EU and with the European Parliament, which criticized weak labor provisions and the lack of coordination with the United States. Merkel’s push for the deal appeared driven by Donald Trump’s “Phase One” agreement, transatlantic uncertainty, and pressure from German corporations heavily invested in China. Soon after, Merkel’s own party called for a stronger transatlantic approach to China, highlighting contradictions between her late push for CAI and the strategic consensus emerging within the EU and NATO.

In 2017, Germany, along with France and Italy, urged the European Commission to establish a common framework for investment screening, motivated by China’s 2016 takeover of Kuka. Berlin ultimately played a leading role in shaping the EU’s investment screening mechanism, formally adopted in 2019. Germany’s national regime, the so-called Außenwirtschaftsgesetz, is among the strictest in Europe and has been used to block or condition Chinese acquisitions. Pressure from German industry also helped steer the EU away from outright “decoupling” and toward a more moderate strategy of “de-risking,” later embraced by both Berlin and Brussels. Germany’s 2023 inaugural China strategy signaled a decisive shift from a business-centric posture to a strategic-industrial approach, aligning with the EU’s economic security narrative and lending political weight to Brussels’ new instruments.

On technology, the EU has increasingly defined China as a systemic rival, introducing protective measures such as semiconductor export controls, 5G security guidelines, and investment screening,—while coordinating closely with the United States on standards and governance in areas like AI and quantum computing. Germany has been central to this agenda yet has prioritized industrial competitiveness, initially delaying restrictions on Huawei and favoring de-risking over decoupling. Thus, the EU’s approach is more security-oriented, while Berlin’s strategy remains industry-oriented. Nonetheless, Germany’s 2023 China strategy shows growing convergence with the EU’s approach to China by recognizing digital infrastructure and supply chain vulnerabilities.

On security, Germany’s China policy has evolved significantly. During Merkel’s tenure, Berlin prioritized “Wandel durch Handel” and economic stability, often softening EU initiatives by downplaying security issues such as Taiwan, the South China Sea, and Beijing’s alignment with Moscow. Under Scholz, Germany adopted tougher language and cautiously endorsed de-risking while protecting corporate interests. Since Merz has taken office, Berlin has aligned more closely with Brussels, dropping “partnership” language, explicitly framing China as a “competitor and rival,” and emphasizing resilience, cyber defense, and critical infrastructure protection—though corporate dependence still tempers a radical strategic break.

Through its dual role as Europe’s largest economy and a key geopolitical actor, Germany has helped steer the EU toward a more balanced China strategy—neither purely values-driven nor narrowly security-focused, but grounded in strategic pragmatism.

About the author

Related Content

Explore the programs

The Global China Hub tracks Beijing’s actions and their global impacts, assessing China’s rise from multiple angles and identifying emerging China policy challenges. The Hub leverages its network of China experts around the world to generate actionable recommendations for policymakers in Washington and beyond.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

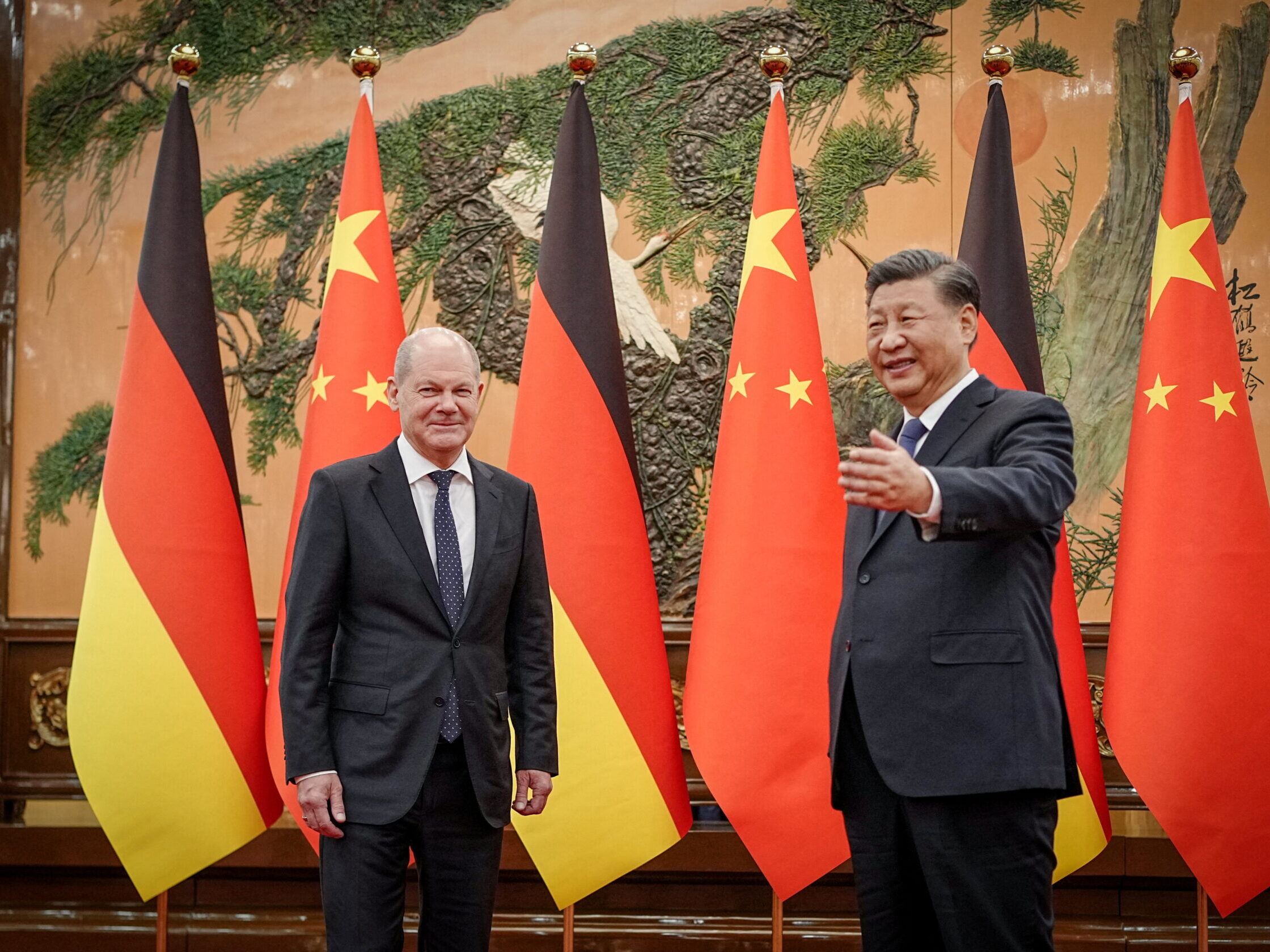

Image: German Chancellor Olaf Scholz meets Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing, China November 4, 2022. Kay Nietfeld/Pool via REUTERS