Systems don’t fail because they are poorly written; they fail because they cannot keep up with the complex and ever-changing needs of a business.

When speaking with Ignacio Brasca, who is a staff software engineer with several years of experience building complex data systems, he emphasized that software behaves much like a biological system—and that the entropy involved in making it grow cannot be underestimated.

As organizations and systems evolve together, developers must plan for long-term change from the start. Ignacio often references Donella Meadows’ idea that “there are no separate systems; the world is a continuum,” arguing that systems only last when they are built not just to work, but to grow.

Determinism of Your Actions

Under the assumption that you don’t depend on services you cannot control, Brasca argues that determinism is one of the most important elements of an effective system.

If you know what you will change and what that change will provoke,” he says, “you can build a system that lasts forever.

This clarity is often what prevents unnecessary abstraction, premature flexibility, and over-engineering. For Brasca, determinism isn’t about rigidity; it’s about having a strong foundation that fosters growth without losing sight of what made your system work well in the first place.

Flexibility vs. Over-Engineering

Flexibility is another area that needs to be approached carefully. Ignacio believes that, in real businesses, flexibility becomes expensive when it’s pursued without a clear understanding of what actual needs will arise over time. Teams often try to design for every possible future scenario, only to discover later that they optimized for the wrong ones.

“The word over-engineered makes us think of unnecessary complexity,” he explains, “but sometimes it’s the opposite. You take the wrong approach to the initial constraints and end up with something that’s simple, robust, and still not functional.”

Brasca relies on a simple framework: “make it work, make it good, make it fast.” Proving that a system solves a real problem comes first. Only then does it make sense to invest in flexibility, performance, or optimization.

Ultimately, flexibility is only worth its cost when it aligns with how the system is expected to evolve. Over-engineering happens when teams design for imagined futures instead of observable change, adding complexity without improving clarity or control.

Maintainability in Practice

Solving for business constraints in theory is one thing; when theory meets practice, things can derail quickly. Ignacio made a pointed observation about this gap:

“Here’s the thing: going wrong is the only part of software engineering that actually makes sense. You never write a program assuming everything will go right. It’s the edge cases that matter.”

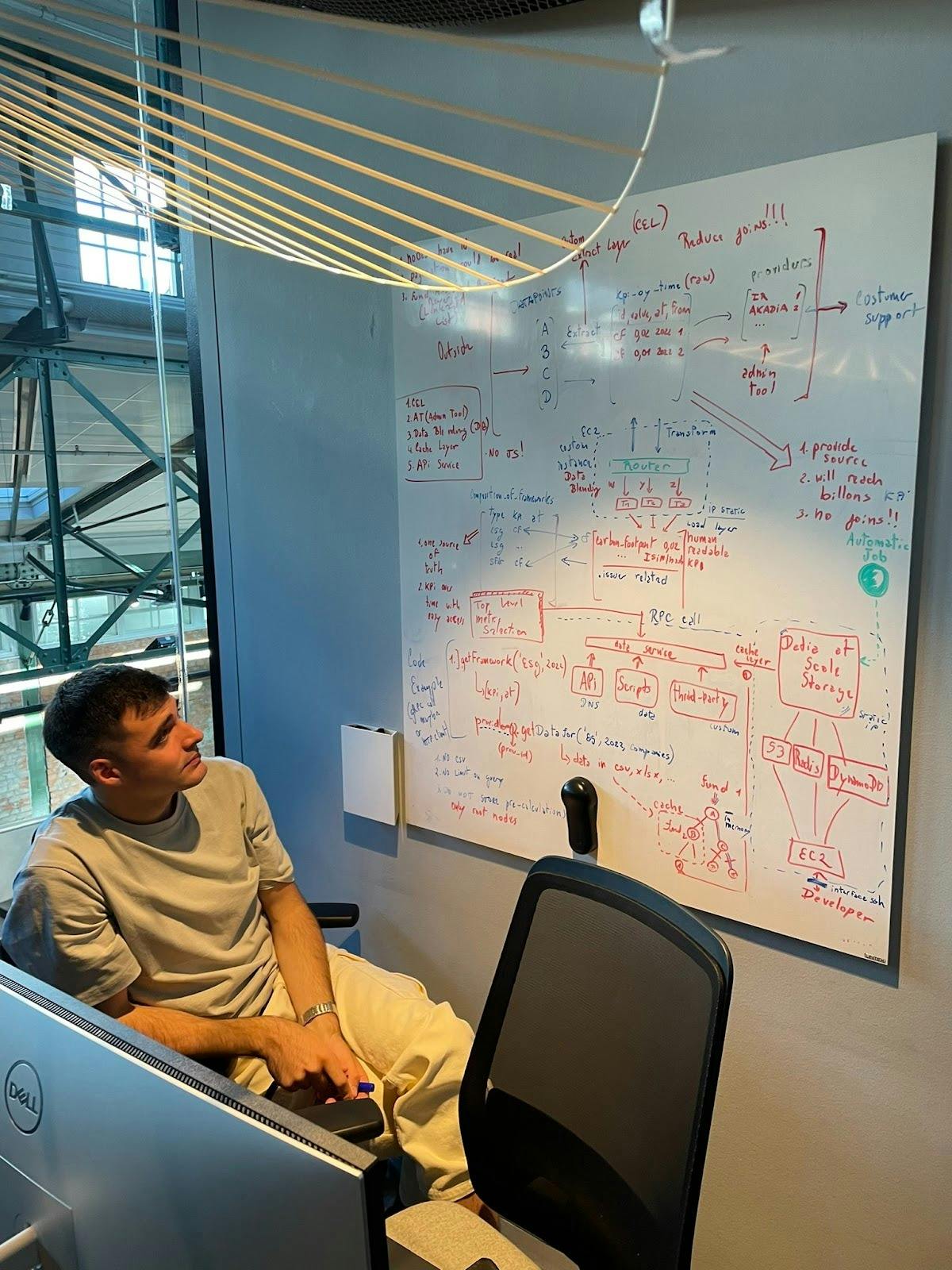

Today, with the help of AI, writing code has become relatively easy. The difficult part is maintaining a clean, solid, and understandable codebase while keeping track of all the changes across a horizontal architecture that allow you to follow through when something goes wrong.

Getting that right, Ignacio argues, is what separates systems that survive from those that slowly collapse. Maintainability is about finding clarity under failure, and getting that right means getting everything else right.

Tooling, DX, and Surviving Change

Getting the code right is only the first step of the process. To scale, developer tooling and experience play a critical role in whether a system survives growth, change, and staff turnover. He notes that engineers tend to be incredibly passionate about their tools and craft; sometimes, trying to over-optimize everything can itself become a problem. However, finding balance and using the right tools can be the solution that removes friction and protects the system from human error.

One decision that significantly reduced long-term friction for his teams was investing early in CI/CD pipelines. While often underestimated, strong guardrails create confidence. Automated checks, validation steps, and consistent deployment processes make it possible to move fast without breaking production.

In that sense, tooling becomes an extension of the system’s philosophy. It reinforces determinism, limits unnecessary complexity, and ensures that growth doesn’t come at the cost of reliability.

Conclusion: Building for Change, Not Permanence

After this conversation with Ignacio, I have come to realize that systems don’t last because they’re clever or perfect; they last because they’re designed with change in mind. Being intentional with decisions shapes how systems age. The belief that architectural decisions are permanent crumbles quickly when you realize that decisions will eventually be wrong and decay over time.

The goal, then, isn’t to predict the future perfectly, but to align systems as closely as possible with the problems they’re meant to solve today, while leaving room to adapt tomorrow. Building lasting software is not purely a technical challenge; it is also an organizational one. Systems need to reflect the values, discipline, and clarity of the teams they are built for.

And in an industry obsessed with speed, novelty, and scale, designing systems that can be understood, maintained, and evolved may be the most enduring competitive advantage of all.

:::tip

This story was distributed as a release by Jon Stojan under HackerNoon’s Business Blogging Program.

:::

![[Webinar] The Smarter SOC Blueprint: Learn What to Build, Buy, and Automate [Webinar] The Smarter SOC Blueprint: Learn What to Build, Buy, and Automate](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiwD8GAdNdNuHeeaGY_XNzQ5R2ImwMvVU46K5gM8t9-q0vuQ4enqi1W5Ljd4D6RktNyAY75SA0gLSrf6oqykbq3lQn5jhZglmqyGYGf3pm6mdHbTSjZoRxPFxG3ruwjYGu6vl9UtgAaORZTIkEliQl1bzeWXt554RsrCKzJlAhyADYV2X_n42rmfAg_Iiig/s1600/soc.jpg)