The idea behind quantum computing has existed for a long while now, with the primary goal being to basically create supercomputers capable of calculating intensive problems almost instantly. While we have yet to see a fully realized quantum computer that comes close to that overall vision, we have seen a lot of progress forward. One big problem that quantum computing has is getting all of the components together in a stable environment and then scaling it up without ruining that stability. The biggest problem here comes in how we approach the scaling of qubits — which are vital to how information and data are processed in quantum computers. However, a new bit of research could help change how we approach that issue by providing an entirely new way to look at scaling qubits effectively.

While we have seen promising progress in futuristic quantum computing and algorithms, the overall scalability of quantum computing is still small, and having actual, tangible quantum computers that can solve some of our most demanding problems still feels a long way off. In fact, some research has noted that we’ll need quantum computers with several million qubits to have any chance at an early commercial application. So how do we achieve that kind of scalability? Well, some believe that a surface approach might be the answer. But to fully understand how that approach will work, and what it will fix, we have to look at the problem a bit more closer.

The problem lies with the qubits

Just like a bit is the most basic unit of information in classic computers, the qubit is the most basic unit in quantum computing. It stands for quantum bit, and up until now, researchers have had an incredibly difficult time scaling it up to a point that will make quantum computing more reliable and effective.

The problem with scaling up the number of qubits needed in a quantum computer is that each physical qubit is especially fragile and susceptible to noise. This means that each of those qubits is prone to errors, and as you add more physical qubits in one place, you’re going to see more noise generated around your quantum operations. As such, you’ll see more quantum information degrading, and degrading faster — in even as little as microseconds, some speculate.

To help overcome these noise issues, scientists have come up with a process known as quantum error correction — which essentially aims to add in a new piece to the puzzle called logical qubits, which are intended to filter out the noise and keep the qubits and how they process information under control. However, researchers have seen somewhat limited success in how they can scale up the amount of physical and logical qubits in a quantum computer while still keeping the amount of errors below a certain threshold.

Finding a new way forward

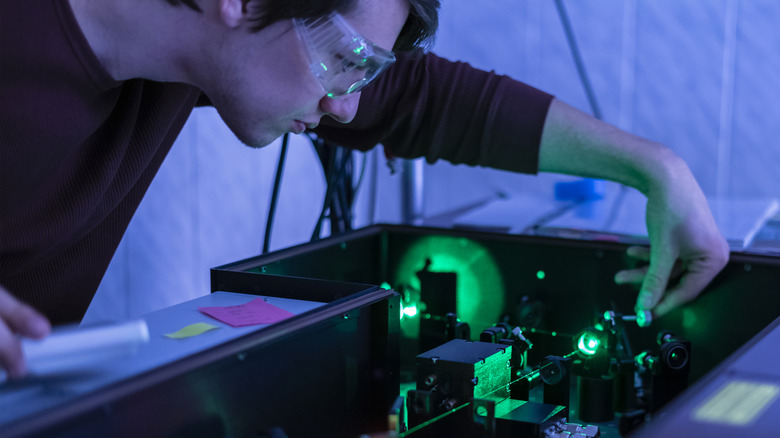

In a new study from Columbia University, researchers highlighted how they created some of the biggest quantum arrays yet by utilizing a surface approach that combines powerful lasers and optical tweezers to capture single atoms, allowing for “unprecedented levels of control over single atoms and molecules.” Furthermore, the success seen in this study comes directly from a new approach to creating the optical tweezer arrays, which the researchers refer to as metasurfaces. These arrays aren’t made up of physical tweezers as you might think of them, of course. Instead, they are actually highly focused beams of light that are strong enough to trap small objects, such as atoms.

Unlike traditional attempts to scale qubits, the metasurfaces utilize two-dimensional arrays of “nano-meter-sized pixels” that take a single beam of light and shape it into a uniform and unique pattern across the entire surface. The team was able to trap 1,000 strontium atoms — which can naturally function as qubits — using the method, and they say it could be scaled up to capture more. The point here is that this method of scaling allows for identical atoms across the board, which should make them more stable. The researchers say their next goal is to capture a hundred thousand atoms.

New approaches like this could further other quantum research greatly. Recently, researchers managed to achieve “teleportation” using quantum supercomputers. While exciting in its own right, it’s ultimately just about sharing data between two computers, though — not quite the “Beam me up, Scotty” moment that any “Star Trek” fans were probably hoping for. But with more scalable quantum systems, it’s impossible to say what else scientists might be able to accomplish.