November 10, 2025

This is the third chapter of the report “Is Europe waking up to the China challenge? How geopolitics are reshaping EU and transatlantic strategy.” Read the full report here.

The European Commission has played a central role in the evolution of the European Union’s (EU) relationship with China since the 1970s. For more than four decades, it championed the normalization and strengthening of bilateral ties in the spirit of engagement. In the past decade, however, it has also emerged as the leading force behind the EU’s shift toward balancing and “de-risking.” In doing so, it has leveraged its trade authority to tackle the areas where China poses the greatest challenges to its member states.

While the EU—and particularly the Commission—initially supported China’s integration into the world economy, it became clear by the early 2010s that the hopes and expectations of the EU’s engagement strategy were not materializing. Instead, China was rising to the status of a great power despite stalled liberalization and limited political integration. Its state-centered and protectionist economic policies presented the EU with structural issues: limited market access, industrial overcapacity and dumping, state subsidies, forced mergers, forced technology transfer, intellectual property theft, and currency manipulation. At the same time, Xi Jinping’s ascendance to power in 2012 ushered in an era of growing domestic authoritarianism and greater assertiveness abroad.

The Commission responded to this challenge in June 2016 with its document “Elements for a new EU strategy on China.” The strategy noted “a lack of progress in giving the market a more decisive role in the economy” and warned that “China’s authoritarian response to domestic dissent is undermining efforts to establish the rule of law and to put the rights of the individual on a sounder footing.” The Commission argued that the EU should therefore “promote reciprocity, a level playing field and fair competition across all areas of cooperation,” press Beijing to respect human rights and the rule of law, and ensure EU unity in dealing with China. Responding to China’s industrial overcapacity, which posed significant challenges to the German steel industry, the Commission launched investigations and imposed anti-dumping duties on Chinese steel imports in July 2016.

Building on growing concerns about China’s unfair economic practices, the Commission has driven the EU’s shift from the engagement strategy towards an engage-and-balance approach and later to a more explicit balancing strategy vis-à-vis Beijing. In response to the structural issues in the relationship with China, the Commission adopted a new strategy in 2019 under President Jean-Claude Juncker. Its joint communication titled “EU-China: A strategic outlook” broke with decades of engagement policy by framing China not only as a strategic partner but also as a competitor and a systemic rival in the so-called European triptych: “[China is] simultaneously… a cooperation partner with whom the EU has closely aligned objectives… an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance.”

Ursula von der Leyen was elected Commission president in July 2019—and her first Commission both followed the essence of the Juncker strategy and expanded upon it. Under her leadership, from 2019 to 2022, the von der Leyen Commission shifted EU strategy from engagement to an engage-and-balance posture. In 2020 and 2021, China’s reputation and EU-China relations suffered a major setback as a result of Beijing’s role in the COVID-19 pandemic and its crackdown in Hong Kong and Xinjiang. At the same time, the first Trump administration negotiated the “phase one” trade agreement with China, which the Commission assessed, “gives America advantages over the EU in terms of trade and investment with China.” As a result, the von der Leyen Commission negotiated the landmark Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) with the Chinese government, which was viewed “as a ‘leveling up” with the US on trade terms relating to China.” Through the CAI, the Commission sought to improve the investment environment for European and Chinese investors and to remedy “level playing field issues” with provisions addressing “Chinese state-owned enterprises, transparency of subsidies, and forced technology transfer as well as on authorisations and administrative procedures.” However, the CAI came under intense pressure from the incoming Biden administration, which saw the agreement as a fait accompli and a potential obstacle to its plans for a coordinated transatlantic approach to China. The European Parliament opposed the CAI on account of China’s bans against several of its members and decided to suspend its ratification. As a result, the EU ultimately abandoned the agreement.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and China’s support for the Russian war effort reshaped European attitudes toward China, prompting another shift in the Commission’s approach. Beginning in 2022, the Commission moved away from the EU triptych, increasingly viewing China as a systemic rival and shifting its strategy from an engage-and-balance posture toward explicit balancing. As von der Leyen underlined at the time, China’s “overcapacities in protected industries… can undermine our industrial base… China has increasingly resorted to trade coercion… China pursues a global order that is sino-centric and hierarchical… China’s assertive posture [in its neighborhood] affects… our own global interests… [We also have to look at China] as a technological competitor, a military power, a global player with a distinct and diverging idea of the global order.” In June 2023, the Commission unveiled its European Economic Security Strategy, which, although nominally country-ambivalent, was in practice largely aimed at addressing China‘s challenges. In the following years, the Commission advanced this strategy by proposing new instruments targeting pressing structural issues with China, including the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI), the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR), and the International Procurement Instrument (IPI).

The second Trump administration’s turnaround on Ukraine, Russia, and trade tensions with the EU sent transatlantic relations into a tailspin beginning in February 2025, putting EU-China relations in a new context for many. Politicians and experts alike began floating the idea of rapprochement between the EU and China. Chinese leaders immediately courted EU officials, arguing that Brussels and Beijing could together defend “the rules-based order” from “unilateralism, protectionism and economic bullying,”—a not-so-veiled reference to President Trump’s tariff war. The Commission’s leadership initially showed openness to China’s overtures, hoping Beijing would make “the right offer” in the form of major concessions on long-standing structural issues threatening the EU’s economic and physical security. In March, EU Trade Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič met with Chinese leaders in Beijing to discuss ways “to improve and rebalance China-EU trade and investment relations.” In April, von der Leyen held a phone call with Chinese Premier Li Qiang to discuss improving bilateral relations. In May, China and the European Parliament agreed to lift restrictions on mutual exchanges, including China’s sanctions on some members of European Parliament.

However, the Chinese leadership showed no willingness to significantly modify China’s positions on overcapacity dumping, market access, and other structural issues, as well as its support for Russia’s war effort. Meanwhile, the Trump administration and the European Commission continued negotiations, edging closer to a trade deal, and the US position on Ukraine began to converge with the earlier transatlantic consensus. In the changed geopolitical situation and the absence of a serious Chinese offer, the Commission concluded that the EU could not pursue a “grand deal” with China as long as Beijing remained unwilling to change its policies on structural economic issues or its role as an enabler of Russia’s war on Ukraine. Commission President von der Leyen and Council President António Costa communicated this stance to the Chinese leadership during the EU-China Summit in Beijing in July 2025.

Trade and investment: Toward an economic security agenda

Trade and investment have been the focus of the European Commission’s China policy, both because of the Commission’s trade competence within the EU’s division of labor and because trade and investment are the core dimensions of EU-China relations. China is the EU’s largest trading partner for goods while the EU is China’s second largest trading partner, with China exporting €519 billion ($609 billion) to the EU and the EU exporting €213 billion to China in 2024. China accounts for 20.5 percent of the EU’s total imports.

In EU-China trade and investment relations, the Commission has had to contend with a number of unfair practices through which China has repeatedly violated the rules of the international economic order, including overcapacity and dumping, state subsidies, restricting market access, forced mergers, public procurement, forced technology transfer, intellectual property theft, and currency manipulation. The von der Leyen Commission has attempted to address these issues in different ways, with tools aligned to its evolving posture. During the first period (2019-2023) when the Commission pursued an engage-and-balance approach, it sought to negotiate the CAI with China. During the second period (2023-2025), when the Commission shifted toward a balancing posture, it adopted an economic security and de-risking approach, designing the European Economic Security Strategy.

In the investment domain, the Commission has adopted the EU Foreign Investment Screening Regulation, which entered into force in October 2020. It serves as the framework for EU-wide screening of foreign direct investment (FDI) to protect security across member states. As with other economic security measures championed by the Commission, implementation has been limited by member states’ uneven participation. Between 2019 and 2020, the Commission then negotiated the CAI with China, addressing some of the unfair practices in the investment area but purposefully excluding similar practices in the trade domain. Under pressure from the Parliament and the Biden administration, the Commission ultimately abandoned the CAI.

In the trade area, the Commission focused primarily on economic security, de-risking, and reducing dependencies. The von der Leyen Commission recognized that many of these issues not only gave China unfair advantages over the EU but also threatened European economic security by undermining the sustainability of EU industries. Accordingly, in 2023, the Commission introduced the European Economic Security Strategy. This document established the EU’s counterpart to the United States’ decoupling strategy: an EU de-risking approach toward China. The strategy called for reassessing risks, re-examining regulations on inbound and outbound investments, and fully implementing export-control regulations.

In recent years, the Commission has advanced this de-risking strategy by creating new instruments, each of which targets a different dimension of the EU’s economic exposure to China. In July 2023, the Commission introduced the FSR to address one of the most serious concerns about Beijing’s economic conduct: the unfair advantages generated by widespread state subsidies to Chinese companies competing globally. The FSR aims “to address distortions caused by foreign subsidies [and] allows the EU to ensure a level playing field for all companies operating in the single market.”

Complementing this effort, the ACI, adopted in December 2023, targets practices of economic coercion. While it does not single out China, most of the practices it targets have been employed by Beijing. The regulation defines economic coercion “as a situation where a third country attempts to pressure the EU or a Member State into making a particular choice by applying, or threatening to apply, measures affecting trade or investment against the EU or a Member State.” The instrument creates a process through which EU businesses or other stakeholders can report instances of economic coercion by third countries to a single point of contact. If the third country refuses to remove the coercion, the Commission can consider a broad spectrum of countermeasures, including “the imposition of tariffs, restrictions on trade in services and trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights, and restrictions on access to foreign direct investment and public procurement.” While this represents a significant step, its effectiveness will depend on actual implementation.

Finally, the IPI, established in December 2022, seeks “to promote reciprocity in access to international public procurement markets.” Under this instrument, the Commission can “investigate alleged measures or practices negatively affecting the access of EU businesses, goods and services to non-EU procurement markets, and consult with the non-EU countries concerned.” If a foreign country’s public procurement practices are found to violate EU and international norms, the Commission may exclude the country’s companies from the EU’s public procurement processes. In its first application, ahead of the EU-China Summit in 2025, the Commission excluded Chinese companies from EU public procurement of medical devices after finding that EU manufacturers were denied equal access to procurement in China.

Technology: Establishing resilience in critical industries

Technology has been a central pillar of the European Commission’s China policy because advanced technologies lie at the heart of Europe’s economic security, industrial competitiveness, and digital sovereignty. Since 2019, the Commission’s posture has shifted from an engage‑and‑balance approach to a more explicit de‑risking approach, framing China as “an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership.” This new strategy aims to reduce critical dependencies and limiting the leakage of sensitive know‑how while keeping Europe open and competitive.

During the engage-and-balance period (2019-2023), the Commission focused on technology protection. When it shifted toward a balancing posture (2023-2025), it adopted the European Economic Security Strategy, launched joint risk assessments for ten critical technology areas—with a particular focus on advanced semiconductors, artificial intelligence (AI), quantum, and biotechnologies—and introduced the January 2024 economic‑security package.

In EU-China technology relations, the Commission has had to address a cluster of persistent risks and practices that mirror—and often intensify—the challenges seen in trade and investment: cyber‑enabled IP theft and espionage against EU networks and firms; leakage of dual‑use and frontier technologies through exports, outbound investment, and research ties; reliance on high‑risk suppliers in critical infrastructure (notably 5G/6G); influence in standards‑setting that can lock in non‑reciprocal advantages; platform‑level risks to users (minors, personal data, democratic processes); and strategic dependencies on critical raw materials that underpin clean‑tech and digital supply chains. These risks—and the “de‑risk, not decouple” approach to mitigate them—were codified in the 2023 European Economic Security Strategy and operationalized through its critical‑technologies list and follow‑on initiatives.

Hardening critical infrastructure began with the EU’s 5G Security Toolbox in 2020, a common risk‑based framework that allows member states to assess suppliers and apply restrictions or exclusions where warranted. In June 2023, the Commission urged full implementation and stated that member‑state decisions to restrict or exclude Huawei and ZTE from 5G networks are “justified and compliant with the 5G Toolbox.” Together, these measures aim to reduce systemic exposure in core and access networks while supporting interoperable, secure deployments across the single market.

Controlling sensitive technology flows has proceeded on two tracks. First, the recast Dual‑Use Regulation modernized export controls, including a human‑rights‑focused “catch‑all” for certain cyber‑surveillance items, while the Commission pushed for tighter coordination and guidance for uniform practice. Second, the January 2024 “White Paper on Export Controls” proposed short‑ and medium‑term steps to make EU controls more effective and more coordinated; the companion “White Paper on Outbound Investments” opened a structured path toward a risk‑based EU framework for outward investments in narrowly defined, security‑relevant technologies. Building on this, the January 2025 recommendation asks member states to review recent and ongoing outbound investments in semiconductors, AI, and quantum technologies, and to share results to inform potential EU‑level action. The problem with these regulations is that the Commission cannot implement them without the active participation of member states. As a result, putting them into practice has been a challenge.

The EU Chips Act forms the backbone of Europe’s effort to rebuild semiconductor capacity and resilience. It establishes a framework of measures to strengthen Europe’s semiconductor ecosystem, including a crisis response mechanism, funding instruments (the Chips Joint Undertaking), and support for design, fabrication, advanced packaging, and skills.¹¹ The aim is to reduce strategic dependencies across both leading‑edge and mature nodes while anchoring more of the value chain inside the EU. Securing inputs for strategic technologies has advanced through the Critical Raw Materials Act, which sets benchmarks for domestic extraction, processing, and recycling by 2030 and, crucially, diversifies supply away from single‑country concentration. This directly addresses Europe’s exposure to Chinese dominance in several inputs essential to clean‑tech and digital industries and complements trade‑defense and industrial policies. The Commission has also moved to protect Europe’s research base and knowledge flows. For instance, a 2022 research‑security toolkit provides universities and labs with practical due‑diligence measures on values, governance, partnerships, and cybersecurity when cooperating internationally.

Horizontal digital‑rule enforcement and baseline resilience complement these measures. Under the Digital Services Act, the Commission opened formal proceedings against TikTok in February 2024 on several risk‑management and transparency grounds, reflecting platform‑level concerns that also feature in EU–China relations. Earlier, EU institutions restricted TikTok on official devices as a protective measure. The EU Artificial Intelligence Act establishes market‑entry guardrails—prohibitions on certain uses, requirements for high‑risk systems, and an AI office—with phased application through 2026 and 2027. In parallel, the NIS2 Directive and the Cyber Resilience Act raise cybersecurity baselines for essential and important entities, as well as for products with digital elements across the single market, reducing the attack surface for data exfiltration and supply‑chain compromise. Finally, the Commission’s standardization strategy seeks to restore European leadership in global technical standards so that interoperability norms reflect EU security interests rather than entrench strategic dependencies.

Security: From partnership to systemic rivalry

The European Commission’s policy on China in the security area may have undergone the most significant transformation of any policy domain in the past few decades. From envisioning a “strategic security partnership” with China in its 2003 communication “EU-China relations: A Maturing Partnership,” the Commission in recent years has come to view China primarily as a “systemic rival. Once focused mainly on the economic aspects of the EU’s external affairs—including trade, investment, aid, and energy—the Commission has shifted its outlook to emphasize the EU’s security interests as the world around Europe has become more complex and dangerous. In recent years, it has begun to look at the EU economy’s resilience in terms of “economic security” and the EU’s technological vulnerabilities in terms of cybersecurity and critical infrastructure security. Furthermore, the Commission has in recent years assumed a significant role in diplomatic, political, and military efforts to guarantee the EU’s physical security vis-à-vis Russia and China, in cooperation with the United States and other allies and partners.

This shift toward security and the process of securitization have been especially prominent since Russia’s unlawful invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The Commission has actively supported Ukraine’s self-defense by mobilizing EU resources and diplomatic efforts. Crucially, it considers China’s role in supporting Russia’s war effort as a direct threat to European security. In President von der Leyen’s words, “China’s unyielding support for Russia is creating heightened instability and insecurity here in Europe. We can say that China is de facto enabling Russia’s war economy. We cannot accept this.” Since 2023, the Commission has introduced anti-circumvention tools and a contractual “no Russia” clause for exporters, banning EU exporters from re-exporting to Russia. In December 2024, the EU’s fifteenth sanctions package listed Chinese entities and individuals that helped Russia procure sensitive components—and subsequent packages in 2025 tightened controls further.

The European Commission is increasingly concerned about Chinese intelligence and espionage activities, citing growing evidence of cyberattacks, human intelligence operations targeting EU institutions, and the infiltration of critical infrastructure by Chinese companies. It has therefore sharpened its response to suspected Chinese intelligence activity, raising the issue directly with Beijing, calling out malicious cyber operations, and urging Beijing to respect international norms. On the issue of cyber espionage, it raised the EU institutions’ cyber baseline by proposing and implementing a new cybersecurity regulation that strengthens networks and boosts CERT-EU’s capacity. Moreover, the Commission ordered TikTok to be removed from staff work devices as a precaution. To address risks from human intelligence, it proposed the “Defense of Democracy” package, including a law requiring transparency from actors lobbying on behalf of foreign governments. On critical infrastructure, it pressed EU countries to apply the 5G Security Toolbox and helped launch an EU-NATO task force to bolster infrastructure resilience.

In response to China’s regional hegemonic ambitions, the Commission has also shifted its approach to Indo-Pacific security. In 2003, the Commission wrote that there was an “undeniable interest in acting as strategic partners” and that “China could play a fundamental role… in promoting peace and stability in Asia. Nearly twenty years later, the Commission and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy published “The EU strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.” The document framed the Indo-Pacific as the EU’s “natural partner region” and expressed concern about China’s aggressive posturing, arguing that “the display of force and increasing tensions in regional hotspots such as in the South and East China Sea and in the Taiwan Strait may have a direct impact on European security and prosperity.” As the challenges posed by China in the region have increased, the connection between European security and Indo-Pacific security has grown. As Commission President von der Leyen recently stated: “Security is more interlinked between the Euro-Atlantic and the Indo-Pacific than it has been in several generations.”

The Commission has taken concrete steps to put this strategy into practice by partnering with Indo-Pacific countries to strengthen the region’s prosperity and security. It brought the EU-New Zealand trade agreement into force on May 1, 2024, and signed a digital trade agreement with Singapore in 2025. It also launched the EU-India Trade and Technology Council to deepen cooperation on trade and digital policy with New Delhi. Through its Global Gateway strategy, the Commission announced new projects with Southeast Asia in 2024, such as a Philippines Digital Economy Package and support for the rehabilitation of a national road in Laos. Moreover, it funds maritime safety and information sharing in the region through the Critical Maritime Routes Indo Pacific program. The Commission has also helped open air links by advancing a bloc-to- bloc air transport agreement between the EU and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Together, these steps aim to strengthen Indo Pacific security and—given the interlinkage—Euro-Atlantic security.

Conclusion

The European Commission has played an outsized role in shaping the EU’s China policy over the past several decades. During the late Cold War and the post-Cold War period, it pursued an engagement strategy toward China and sought to integrate Beijing into the international economy and the rules-based world order. By the 2010s, however, it recognized—alongside the US government, other EU institutions, and member states—that its engagement with China had not led to Beijing becoming a “responsible stakeholder.”

Instead, China took advantage of its “partners,” violated the rules of the international economic system, and emerged as a global great power. In response, the European Commission has driven the EU’s gradual shift away from engagement with China—first to a mixed engage-and-balance posture and, more recently, to a strategy centered on balancing and de-risking. Intensifying US-China strategic competition—and the recalibration of US China policy under the Trump and Biden administrations—have significantly pushed the Commission (and the EU more broadly) in this direction. This shift was further accelerated by Russia’s unlawful aggression against Ukraine in February 2022 and by China’s support for the Russian war machine. While periods of perceived US disengagement from global affairs—and from Europe—have at times made the Commission hesitant to pursue a balancing approach toward China, these developments have nonetheless strengthened its resolve to defend EU interests more firmly.

Similarly, China’s economic practices have pushed the Commission toward a more assertive and security-conscious stance, aligning it more closely with US balancing efforts. By advancing this shift and shaping the EU’s de-risking strategy, the Commission—especially under President Ursula von der Leyen’s leadership—has assumed a central role in steering the EU’s China policy to protect the bloc’s economic, technological, and security interests.

About the author

Related content

Explore the programs

The Global China Hub tracks Beijing’s actions and their global impacts, assessing China’s rise from multiple angles and identifying emerging China policy challenges. The Hub leverages its network of China experts around the world to generate actionable recommendations for policymakers in Washington and beyond.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

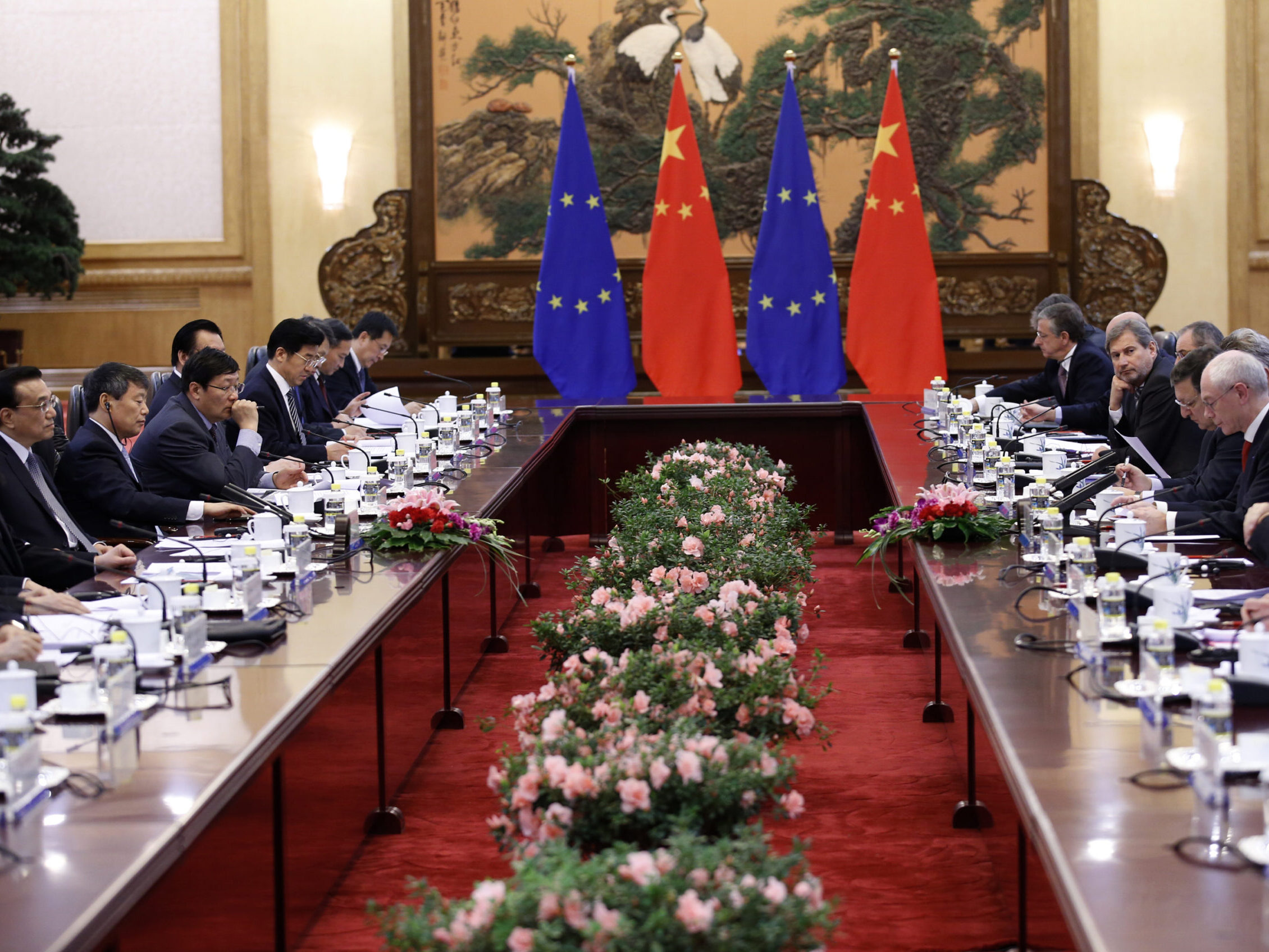

Image: China’s Premier Li Keqiang (4th L) meets with European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso (3rd R) and European Council President Herman Van Rompuy (2nd R) at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, November 21, 2013. REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon (CHINA – Tags: POLITICS BUSINESS)