In 2012, Hurricane Sandy devastated the Caribbean Sea and reached the coast of New York. There he left floods, power outages and spectacular photos. Of all of them, there was one especially amazing one that went viral, but there was a problem: it was false. She was not the only one who sneaked into networks.

That image was just one more example of what we have seen before and after: great phenomena and events end up generating floods of content, some of which are not real.

There are many reasons why people take advantage of these moments to spread fake images, but at least before, achieving credible images and videos was expensive. Only advanced users of applications like Photoshop or Final Cut/Premiere could achieve convincing results, but AI, as we know, has changed all that.

We have been warning about this problem for some time: distinguishing between what is real and what is generated by AI is increasingly difficult. and these days we have had the last great example of this trend.

Anatomy of a deepfake

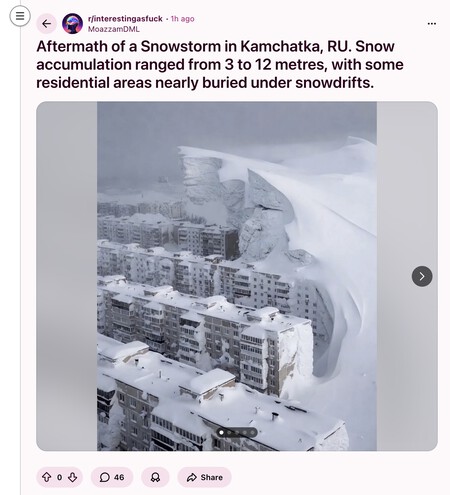

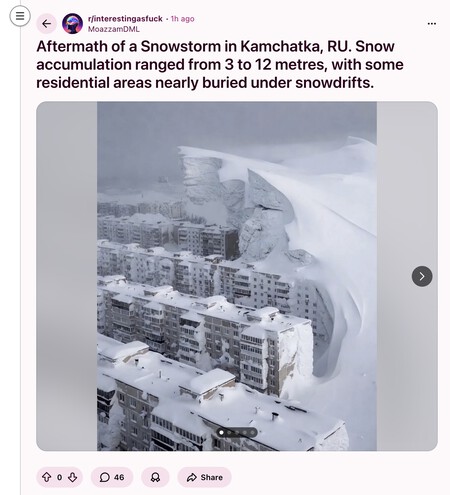

The Kamchatka Peninsula, in the far east of Russia, has experienced a historic snow storm. The worst in decades, according to records, with snow levels exceeding two meters in various areas, according to Xinhua.

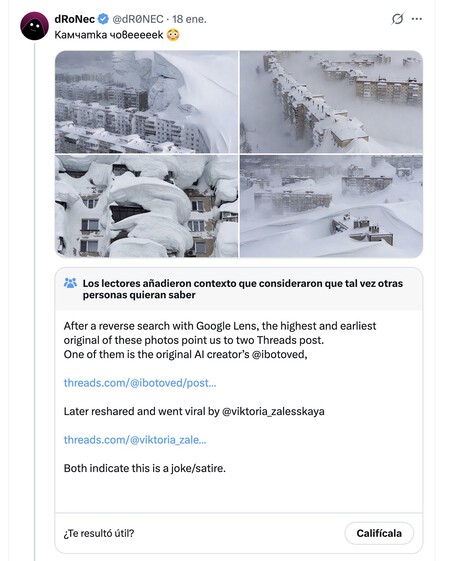

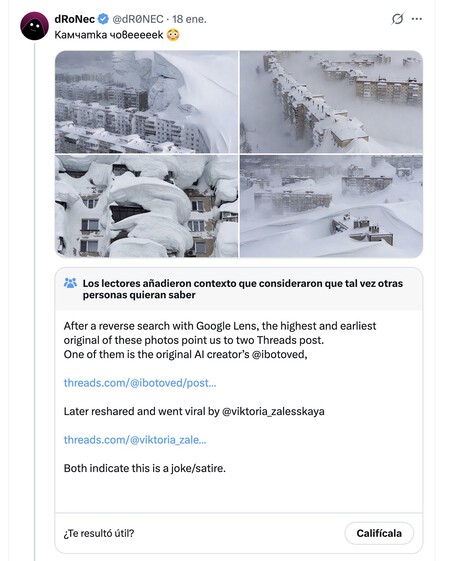

Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, the administrative, industrial, and scientific center of Kamchatka Krai, has especially suffered these consequences, and residents of the region have spread images of what has already been dubbed the “snow apocalypse” on social networks. These images spread in the news media and social networks and that were real—often more “mundane” and much less spectacular—contrast with others that theoretically also showed the state of various points in the region but that are actually generated with AI.

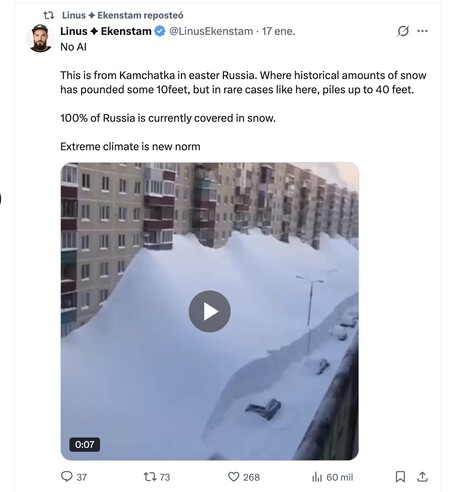

That video, for example, was shared a few days ago by Linus Ekenstam, an influencer who often shares news and reflections on AI. He republished that video and claimed that it was real, but soon several users indicated that the video was actually created by AI.

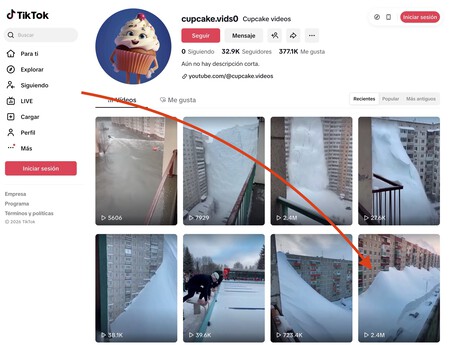

Ekenstam argued that the theoretical AI error that it pointed out in the user was not such, and that where he lives there are poles near the streetlights. He therefore tried to defend that for him the video was real, but others suggested that it was not. The definitive proof: a user linked to the theoretical original video, which apparently originated from a TikTok account dedicated precisely to disseminating AI-generated content that seems real.

The crucial thing about that fake video is that it is spectacular, but not overly spectacular. It is, to a certain extent, believable, and when the image and the camera movement itself is so convincing, it is difficult to think that “maybe it is generated by AI.”

With this snow storm experienced in Kamchatka, unusual images have been shared on networks, much more typical of a dystopian Hollywood movie than a real natural phenomenon. A priori the images may even seem coherent, but a more detailed – and above all, more critical – examination makes it easier for us to realize that perhaps these images are not as real as they seem.

In fact, the most striking images shared on social networks and that accumulate thousands of retweets and likes on X, for example, contrast with those published in traditional media, which tend to be, as we said, much less striking and much more mundane.

Spanish media such as OndaCero or OKDiario have published in their digital media or in their social media accounts some images and videos generated by AI without realizing that these videos actually had their origin in the aforementioned TikTok account that has managed to spread like wildfire.

Debates about the possibility that certain images could be real have been frequent, for example on Reddit, where users shared, for example, an amazing capture that, when analyzed in detail, seemed generated by AI.

The avalanche of “citizen journalism”, which can be well-intentioned and very important at times, contrasts here with the role of the media, which has an enormous responsibility in acting as trusted sources of information.

Even they (and we) can fall into the trap, and here once again The best thing is to start distrusting what we see on our screens, because it may be false content. The videos that appear in some media such as Sky News or La Vanguardia are combined with others that (at least a priori) seem real, but that at this point also require rigorous examination.

Our brain betrays us and technology knows it

There are several well-studied psychological phenomena and cognitive biases that explain why we believed in fake news in the past and now the same thing happens to us again with deepfakes.

It doesn’t matter if we know (or at least rationally suspect) that these images and videos are false: technology and especially AI precisely exploit these biases. Among them the following stand out:

- Confirmation bias: we believe what fits with what we already believe. Our brain does not seek truth as much as internal coherence, so if a piece of news reinforces our ideology, we lower the level of potential criticism, but if it contradicts it, we analyze it with a magnifying glass or directly discard it. The problem here is that AI can generate tailor-made content adjusted to each narrative.

- Illusory truth effect: here it happens that “if I have seen it many times, it will be true.” Repetition increases the feeling of truthfulness, not actual truthfulness, and it is something that, for example, social networks, machines for repeating hoaxes, make the most of. Again, AI facilitates the mass production of the same lie with minimal variations.

- We believe what we see: This is what some call perceptual realism. We trust too much in the visual, and hence the famous saying “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Images are processed much faster than text, and critical thinking comes after the emotional reaction, as Daniel Kanheman argued. in his famous ‘Think fast, think slow’.

- Cognitive load: related to the above, thinking critically is tiring, and that means that when we are tired, distracted or in a hurry we use mental shortcuts. The famous and worrying doomscrolling takes advantage of this trap very well, and both fake news and deepfakes are designed to be easy to believe, not to be analyzed.

There is more, of course. AI already generates convincing results but in addition – especially in text – its security when communicating and expressing them activates an authority bias. It is as if it seems more reliable than if it were told to us by a human expert who, for whatever reason, does not have the facility to communicate his knowledge skillfully.

Content generated with AI also takes advantage of those great phenomena and events that maximize the emotional impact, and there is also the fact that when many people share it it is because “it must be true” and because we tend to believe that it is others who fall for these deceptions, not us.

As that one said, be careful out there.

In WorldOfSoftware | It is impossible to distinguish whether this video with the ‘Stranger Things’ actors is made with AI or not. That’s a problem