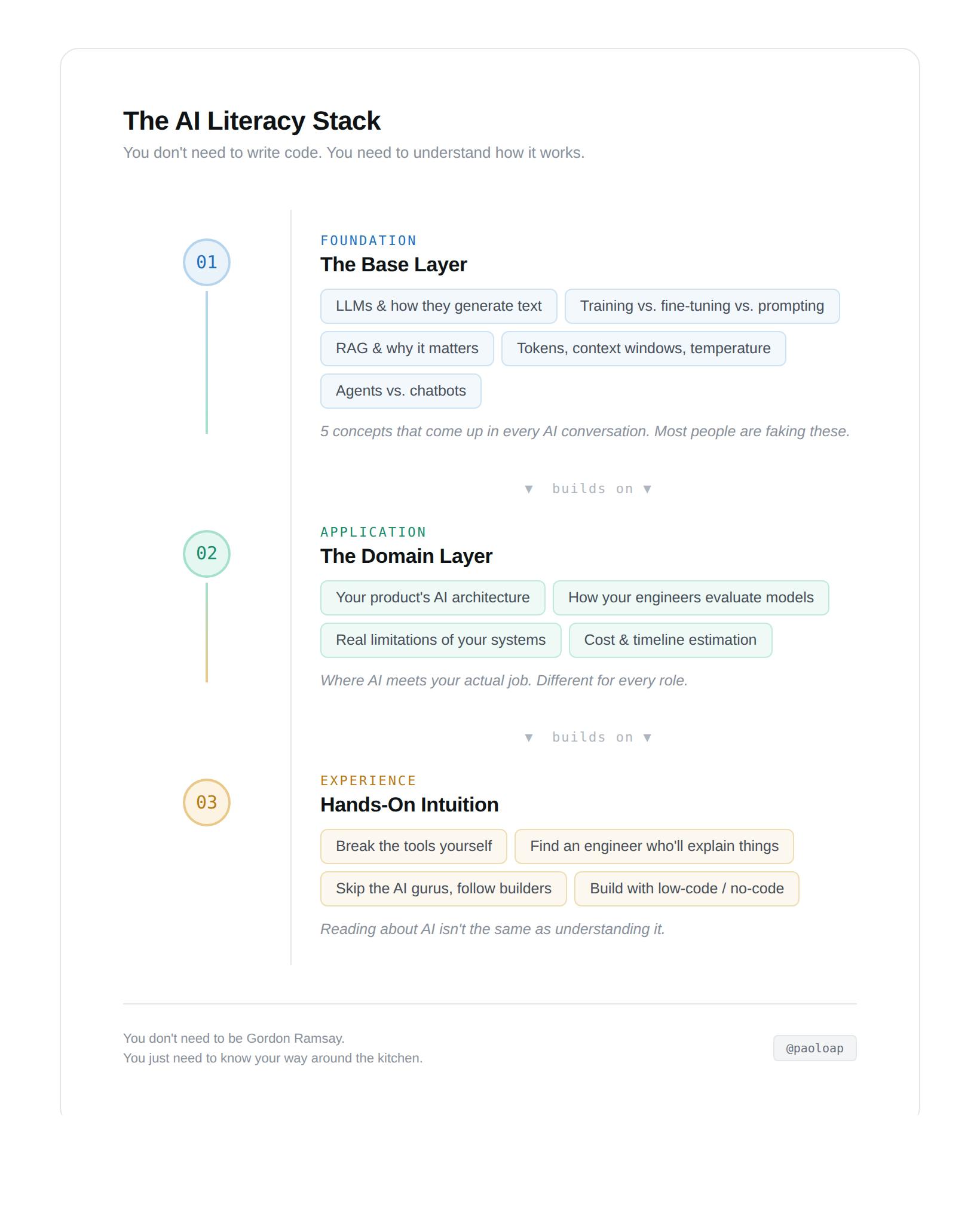

The software sector is experiencing the worst market sell-off since the depths of the 2008 financial crisis, but this time the trigger isn’t the banking collapse, but artificial intelligence.

The US sector fell 14.5% in January, its worst monthly performance since October 2008. The sell-off accelerated in early February, with a further 10% decline in less than two weeks.

At the heart of the defeat is growing investor concern. Many fear that AI tools will not only improve existing software products, but also erode parts of the subscription-based business models that have underpinned the industry’s growth for more than a decade.

In the United States, some former industry high-flyers have experienced dramatic turnarounds.

Unity Software, which provides tools for video game developers, cybersecurity group Rapid7 and customer engagement platform Braze have each lost more than half their market value since the start of the year.

Even the giants have not been spared. Palantir, long considered an AI whistleblower, along with major companies like Salesforce, Intuit and ServiceNow, is down about 30% this year.

One of the biggest triggers for the industry sell-off was Anthropic’s unveiling of new enterprise plugins for its Claude AI assistant in January.

The announcement suddenly prompted investors to ask an uncomfortable question: If AI can do what these software platforms do, why do we need these platforms at all?

Related

Europe’s wider software sector is estimated at around €300 billion and is highly concentrated in a handful of companies.

That concentration makes every percentage drop more visible – and more painful.

German flagship technology group SAP is by far the largest European software company with a market capitalization of approximately €200 billion.

Shares in SAP are already down about 20% this year and 40% since the February 2025 peak.

In terms of market value, SAP has wiped out €188 billion in the past year alone, almost half of its current capitalization.

Even more worrying than the number is the trend: SAP is heading for the ninth consecutive month of decline. That has never happened in more than 30 years of trading.

For a company long seen as a pillar of European tech resilience, the symbolism is stark.

France’s Dassault Systèmes, known for its 3D design and engineering platforms used in aerospace and manufacturing, ranks second among European listed software groups, with a market capitalization of around €24 billion.

Shares are down about 25% since the start of the year and are heading for a fifth consecutive month of declines – the longest losing streak since 2016.

Sage Group is in third place. The British accounting software provider is down about 25% this year, including a 17% drop in February alone, putting the stock on track for its weakest monthly performance since July 2002.

British information and analytics group RELX suffered a sharp 17% drop in one session earlier this month – its steepest daily decline since 1988 – and is now on track for what could be its worst month on record.

While European software giants are under pressure, mid-sized companies are feeling the pressure even more acutely.

Smaller companies tend to have smaller customer bases and less diversified revenue streams, meaning shifts in investor sentiment can translate into sharper stock price swings.

France’s Sidetrade, which uses artificial intelligence to help companies manage order-to-cash processes, is down almost 50% since the start of the year, making it the hardest-hit name in the European software space.

Sweden’s Lime Technologies, a CRM provider focused on the Nordic region, is down almost 38%, while Denmark’s cBrain, known for its digital platforms used by government services, has lost about 35%.

Norway’s LINK Mobility Group, which provides communications and messaging platforms for businesses, and SmartCraft, which provides cloud-based tools to the construction industry, are down about 32% each.

French group 74Software, which specializes in API management and digital financial integration, has seen a similarly steep decline.

The debate among experts reflects the uncertainty in the market.

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has dismissed the idea that AI will replace software as “the most illogical thing in the world,” arguing that AI will improve existing systems rather than eliminate them.

Wedbush Securities said markets are pricing in an “Armageddon scenario” that appears disconnected from business reality, noting that companies won’t rip out software infrastructure overnight.

JP Morgan strategists have similarly suggested that investors discount worst-case disruption scenarios that are unlikely to materialize in the near term.

Veteran Wall Street investor Ed Yardeni said markets have moved from “AI-phoria to AI-phobia.” This indicates that while sector valuations now appear more compelling, earnings expectations may not yet fully reflect the potential slowdown facing software companies.

Still others urge caution. Goldman Sachs strategist Ben Snider has warned of “long-term downside risks”, drawing parallels with sectors such as newspapers and tobacco that are underestimating structural changes.

The expert highlighted a fundamental market rotation, with investors rapidly exiting AI-exposed software stocks and reallocating capital to cyclical and value-oriented sectors that are more closely linked to the “real economy.”

The key question is whether this marks a necessary repricing of a sector that has benefited from years of high valuations – or the early stages of a more structural reset, powered by AI.

For investors, the current sell-off goes beyond quarterly earnings or interest rate expectations. It reflects a deeper uncertainty about how value will be created and captured in an AI-driven economy.

If AI tools reduce the need for multiple layers of business software, margins and pricing power could come under pressure.

If AI instead improves productivity within existing platforms, today’s correction may prove excessive.

History shows that technological transitions rarely eliminate entire sectors. More often, they change competitive hierarchies.

Some companies will likely emerge stronger, others will struggle to defend their pricing power or relevance.

The software industry won’t disappear overnight. But the winners and losers will likely look very different from those of the past decade.