In Google Calendar’s Secret Engineer Weapon: Restraint, I praised Google for unapologetically saying “no” to the temptations of modernity.

Thanks for reading Fullstack Engineer! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribe

"Use a frontend framework."

No.

JavaScript.

"Use Typescript."

No.

Javascript.

"Use a trendy CSS tool."

No.

CSS classnames.

"Give us a native desktop app."

No.

Browser.

"Give us dark mode."

No.

"Make it really fast."

No.

Their commitment to simplicity has helped GCal to defend its position as the default calendar for billions of regular people.

For API clients, however, that same simplicity makes life tragically complicated.

How that complexity creeps in, and what we can learn from it as builders.

The Problem: Keeping Data In-Sync

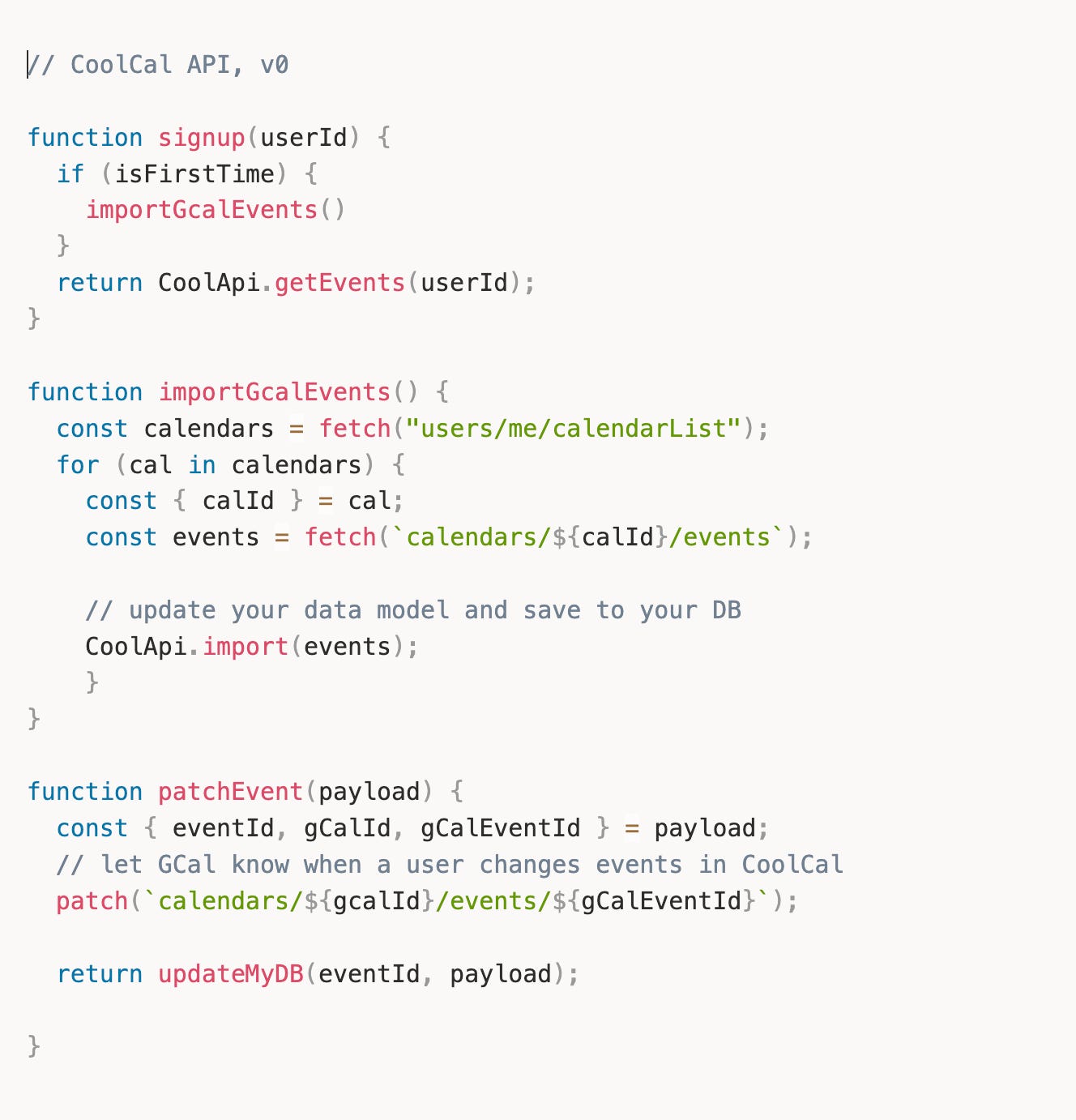

You’re building a cool new calendar called Cool Calendar.

To help users get started, you allow them to import their existing Google Calendar.

This’ll require access to your users’ Google Calendar data.

You look at the GCal API and see the typical suspects: “Cool,” you think. “I just gotta get the calendarId, then get all the events for that calendar. When I need to update an event, I’ll use the eventId from the GET events response.”

You could do all this with a few simple functions:  It works! All the events are in your DB, and they also show up in the user’s GCal after a user updates an event from your UI.

It works! All the events are in your DB, and they also show up in the user’s GCal after a user updates an event from your UI.

You open the GCal app, create a new event called “Celebrate at Denny’s,” and look forward to your cinnamon roll pancakes.

Cool Cal app is open, but the new event doesn’t show up.

Your empty stomach sinks as you realize you only implemented half the solution (CoolCal → GCal).

You still need to ensure that GCal changes propagate to Cool Calendar (GCal → CoolCal).

Denial

You know that others have encountered this use-case before, so you revisit the GCal API docs.

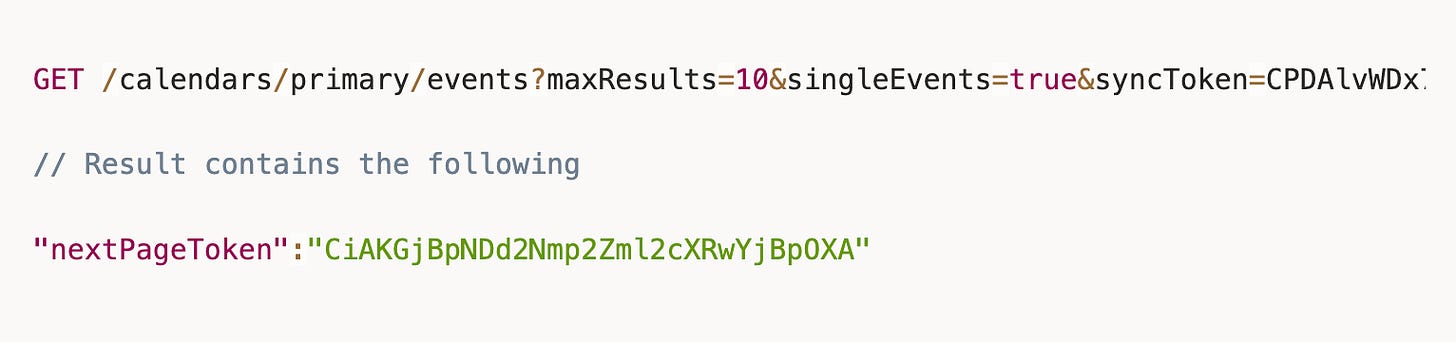

Thankfully, you find a guide called “Synchronize resources effectively.”

The guide is short, which puts you at-ease.

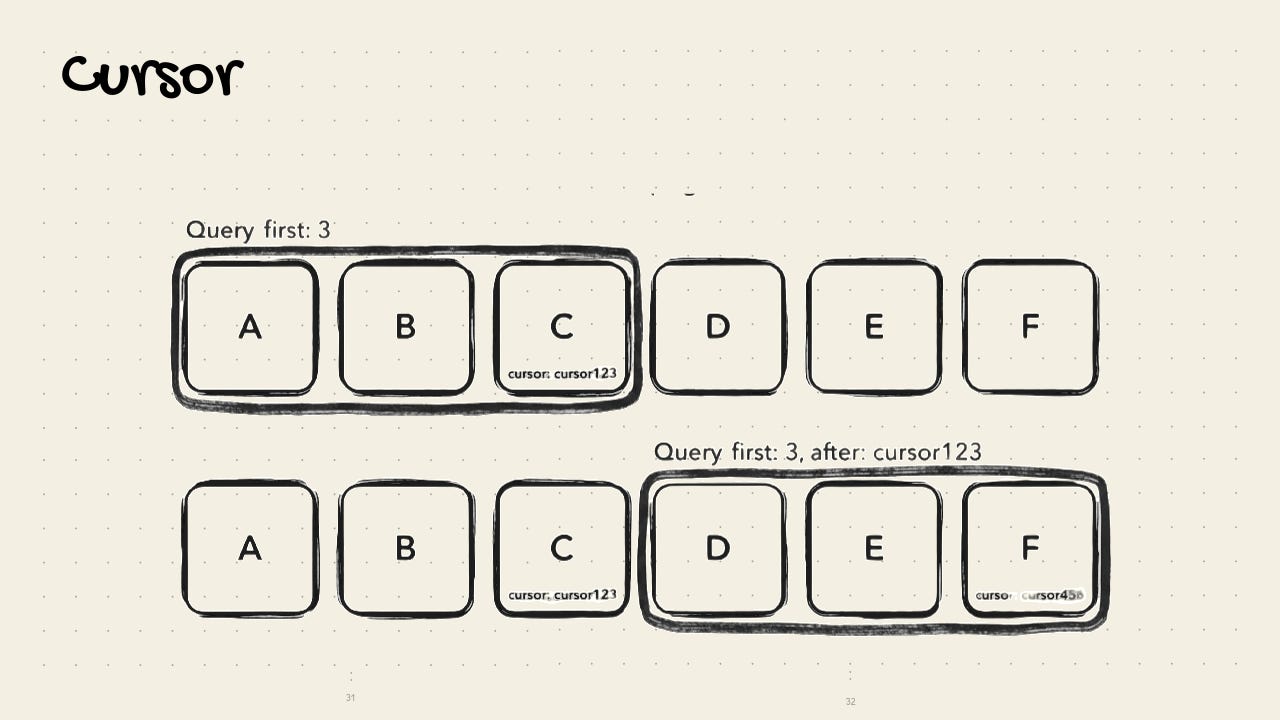

It looks like you just need to add a few more calls.  Since you don’t know how many events were updated or when they were, you know you’ll need a loop to fetch all of them.

Since you don’t know how many events were updated or when they were, you know you’ll need a loop to fetch all of them.

Makes sense.

Thankfully, the docs include a full snippet of this in Java.

It even uses the do-while looping strategy, which makes you feel smart.

Surely you can just convert that to JavaScript and move on.

Anger

It’s been an hour, and you’ve successfully converted the snippet to a JavaScript function called syncGcal() and updated your API.

It works!

Whenever you run syncGcal(), a user’s new GCal data is added to CoolCal.

You resolve to include the New York Style Cheesecake for your troubles.

As you’re on your way out, a few questions arise in your tired brain…

- The

syncTokenisn’t persisted anywhere syncGcal()only works when it’s called manually

How often should I run syncGcal()?

Every hour?

Every minute?

Where will I store the token?

Local storage?

The user collection?

A new collection?

What happens if the token becomes invalid?

Can I keep retrying?

Would I need to do a full import as a backup?

What about quota limits?

What if a user makes a change during this process?

You become enraged — at the guide for not warning you about these edge cases, then at your naiveté for assuming it should.

Bargaining

“I’m not alone — I can reach out for help,” you say to yourself, just like you practiced in therapy.

You’re confident that the API docs will have a method called syncResources() that you overlooked.

Or it’ll be offered as a service? Like some YC company that’ll magically sync all your data for you.

At the very least, there’ll be a Richard Stallman disciple who has an MIT repo you can point Claude to.

> clone the two-way sync stuff from github.com/stallman-cal. no bugs.

Depression

The official docs are bare.

All the YC companies are building agents.

Stallman doesn’t trust your for-profit calendar app.

(There’s an MIT project called Compass Calendar, but it only has 200 stars. Can’t be trusted.)

No one cares about your two-way sync feature.

You are, in fact, all alone.

A single tear falls onto your mechanical keyboard as you realize you won’t be going to Denny’s today.

Acceptance

After homemade French toast and a postprandial walk, you come to terms with your destiny to act like a real engineer and do it yourself.

A few weeks later, it’s finally done.

But you still can’t stop wondering

“Why did GCal do it this way?”

“Did it have to be this complicated?”

The Requirements

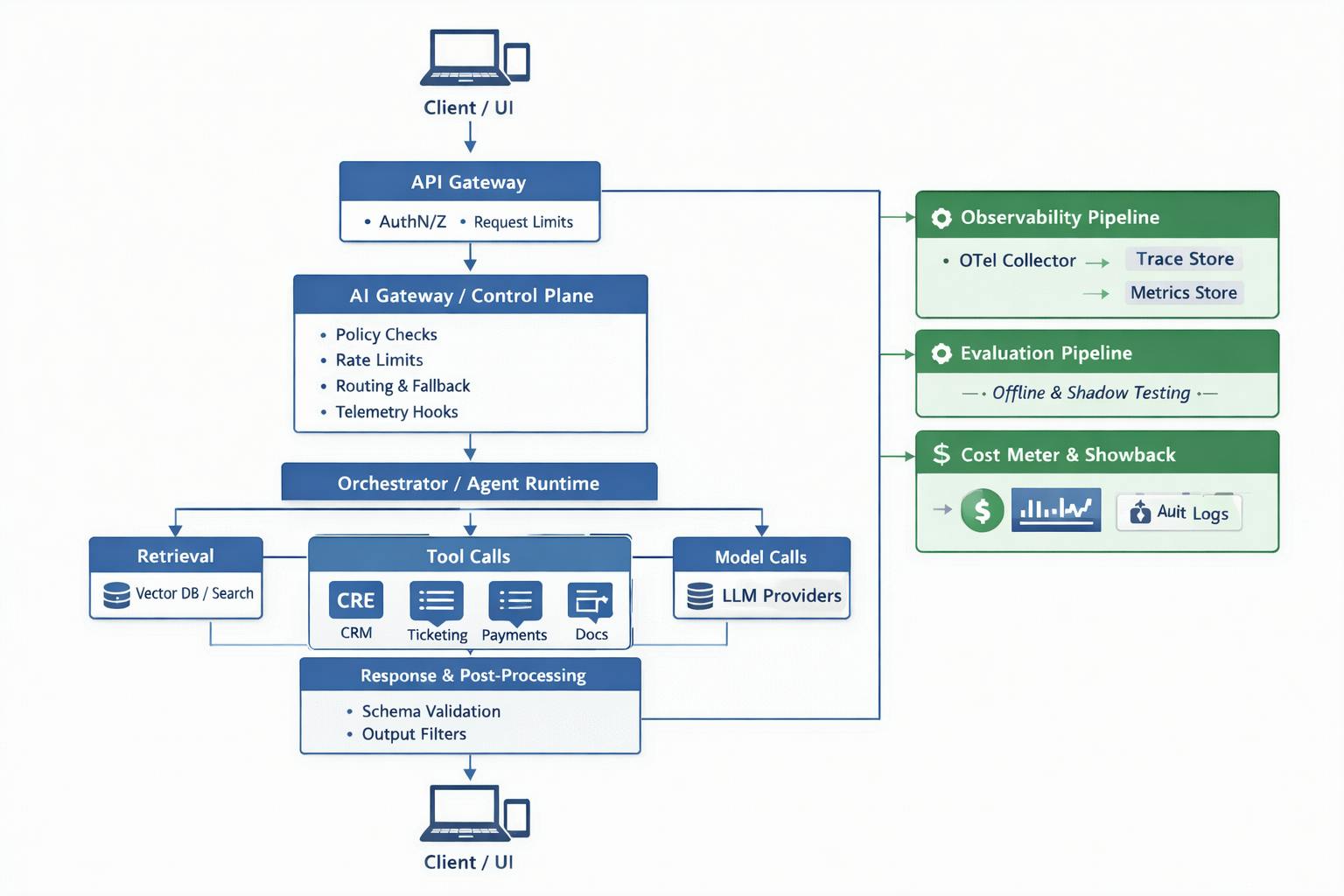

You put yourself in Google’s shoes by reverse-engineering the requirements in the form of a Product Requirements Doc (PRD).

The Solution

That was fun, so you document the solution to meet those requirements as a Technical Design Doc (TDD).

Analysis

Finally, you feel qualified to say whether GCal’s “Give ‘em a token” solution was a good one.

Strengths of Token Pagination

Opaque tokens protect the client from overwhelm. They can hide the complexity from the client so they don’t need to understand everything (multi-region replication, for example)

Cleanly handles deletions. By controlling when tokens expire, GCal can ensure clients always see deletions during incremental sync. Timestamp-based approaches can’t make this guarantee.

Easier implementation changes. Google can completely change its storage backend, sharding strategy, or topology without affecting clients. This surely made the migration from NoSQL (Megastore) to NewSQL (Spanner) easier in the 2010s (highscalability.com).

Weaknesses

Push is disconnected from sync. The webhook tells you something changed, but not what. This means every push notification triggers a new incremental sync call. This gets chatty when power-users make frequent tweaks. Why not include a lightweight diff in the push payload itself, or at least indicate which event IDs changed?

Some filters are incompatible. Incremental syncs are incompatible with the timeMin and timeMax parameters. You must choose one method or the other. This is a bummer for humans, who think in terms of time more easily than in tokens.

No partial sync recovery. The page tokens are ephemeral. If a client crashes mid-pagination (after page 3 of 7), they must restart the entire sync. For large calendars, this is painful. An alternative would be durable page tokens that survive across sessions, or checkpointing the sync progress.

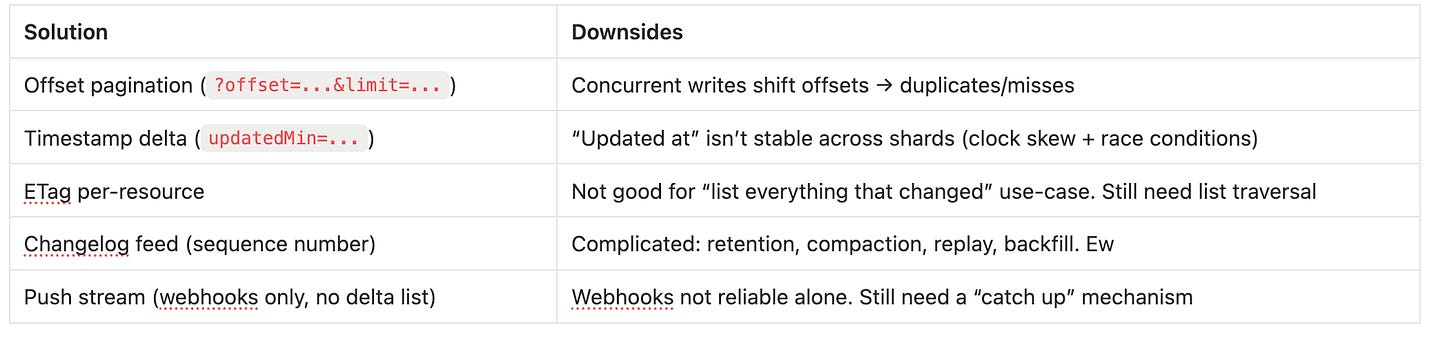

Alternatives (and why they weren’t used)

Bottom Line

The sync token + cursor pagination approach is a pragmatic, battle-tested pattern that works. It’s the same pattern used by Microsoft Graph (delta tokens), Stripe (pagination cursors), and most enterprise APIs.

Google chose it because it lets them hide internal complexity while providing “good enough” sync semantics for 99% of calendar use cases.

The alternatives (event sourcing, CRDTs, OT) would only make sense if GCal required real-time collaboration or true offline-first P2P sync.

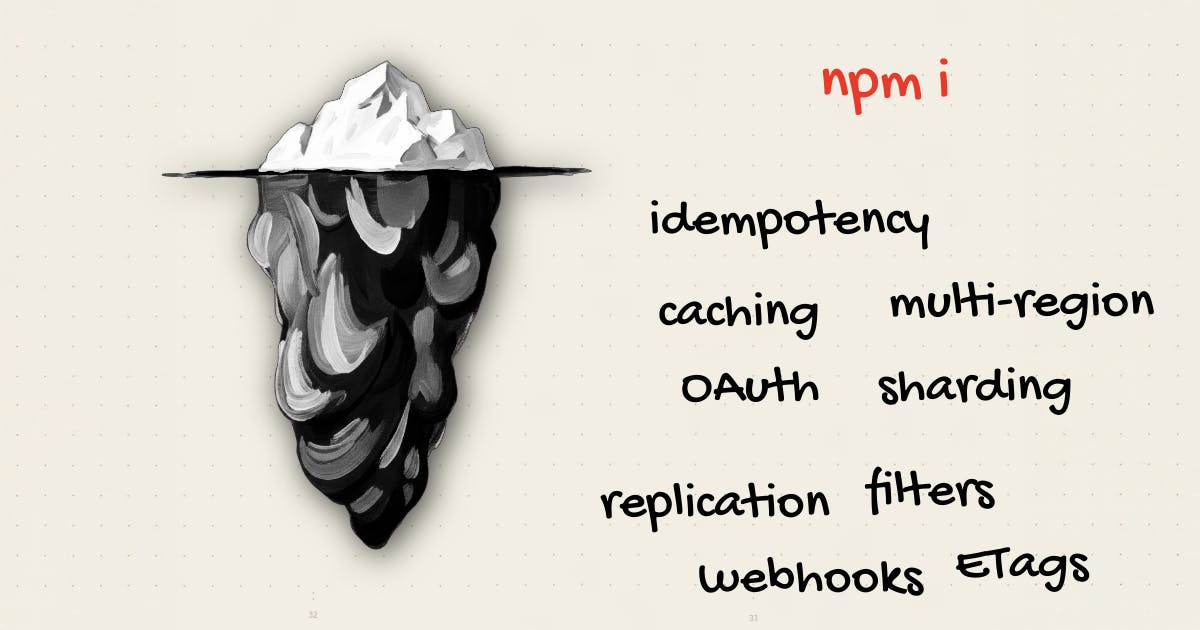

The Full Picture

If Google’s goal with GCal were to generate revenue, they’d offer more docs, videos, and webinars. There’d be a handsome Developer Advocate, tiered API pricing, and a Client Success Team. I’d see billboards around SF that just say,

npm i gcal

But Google’s goal with GCal is less ambitious:

>> Don’t annoy regular users so much that they download Apple Calendar.

It’s not fair to expect so much out of a free API.

It’s amazing that you can integrate with GCal in the first place

GCal honors its responsibility as a foundational part of your app by prioritizing reliability over adoption convenience:

- Not many failures occur.

- The API does what its docs say, even if they don’t say much.

- They don’t surprise you with breaking changes

Still, there is a gap between the developer’s expectations and reality when they first think, “I know, I’ll just integrate with GCal.”

Currently, the developer has to close that gap with time, effort, and a loss of innocence.

But Google could reduce the pain by providing more resources.

For example, the docs could offer more implementation guidance.

The code samples could evolve from bare repos to demo applications.

On balance, keeping the API simple was the right move.

A primitive API might annoy power users.

But if it doesn’t affect UX, revenue, retention, or the brand, then keep it simple.

Takeaways for Builders

When creating a public sync API

Keep it boring: use existing standards

We’ve seen here how GCal’s API is built on cursor pagination and sync tokens. Its event model is also built around established standards: CalDAV, iCalendar, and RRULEs.

Instead of inventing their optimized versions, they stuck with the basics. This is a big reason why there’ve been so many successful GCal integrations since their API went public in 2006 (unlike Yahoo).

Use cursor pagination when the data is a moving target

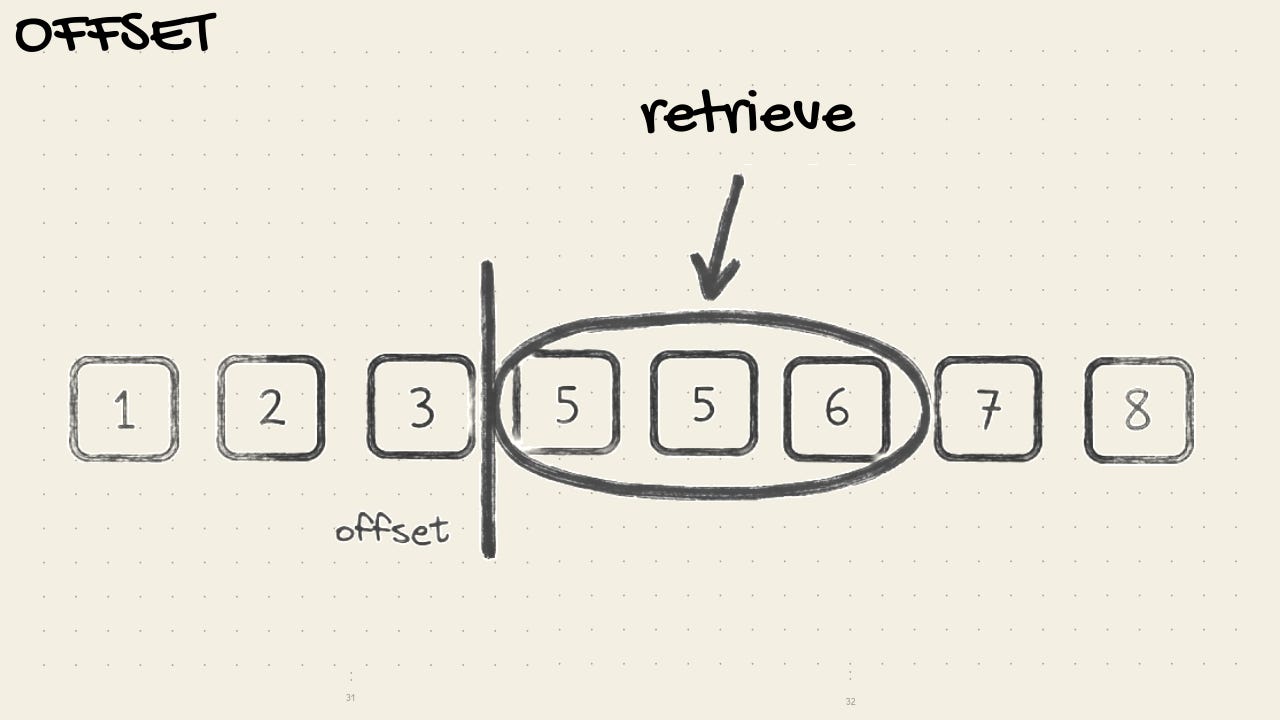

When writes happen while you read, you need consistency across pages to avoid duplicates and missed rows.

Examples: Calendars, feeds, audit logs, append-only streams.  Use offset pagination when the data is stable

Use offset pagination when the data is stable

If data is static and doesn’t have concurrent writes, you can get away with a simpler approach.

Example: Search results with page numbers, admin table for small data.  Don’t oversell the API

Don’t oversell the API

You know how it feels to get excited in the morning to finish a PR and then for a hike … only to realize that it’s more complicated than you thought and not see daylight until the next afternoon.

Google’s API doesn’t promise to do everything for you.

The end product will sell the API: spend your time delighting your users with your product before worrying about delighting the devs who integrate with it

Don’t break things

If your integration is foundational to another person’s product, then go slow.

Spend more time testing the migration.

Get feedback on the docs before launching them.

Send “heads up” emails and terminal messages so no one is surprised.

This requires an identity shift from “crackhead vibe coder” who breaks things in prod to “disciplined software engineer.”

You won’t always get it right, but take the responsibility seriously.

One breaking change will do more damage than three features will do good.

GCal’s API is stable, so my sleep score thankfully hasn’t dropped since using it.

When integrating a public sync API

Don’t start with an integration

“But my users won’t use my app unless it integrates with the tools they’re already using.”

Maybe, but let them tell you that.

Adding an integration is an expensive side quest on your product-market fit journey.

If the value prop is good enough, they’ll have no problem creating a new account and adding data from scratch.

Accept that Pareto is right

In other words, the last 20% of tasks will take 80% of the time.

The surface for edge cases and gotchas widens as you implement.

Google’s docs aren’t the only ones that will tempt you into thinking that things can be simple AND free.

Temper their promises by considering retries, idempotency, fallback, delta syncs, offline, token invalidation, quotas, and conditional requests (ETags).

You don’t need all of those for your MVP, but expect that they’ll come up eventually.

Simplicity for one party means complexity for another

Simple UI → complex backend

Good for regular users → difficult for power-users

Simple pricing → complex R&D

Simple API → complex integration

The next time you think, “I’ll just use this free API, it looks straightforward,” remember:

It’s either free or simple; Someone always pays.

Now go get your pancakes.